One of the great mysteries of history yet to be fully solved is the role of President Donald Trump in the Covid pandemic and policy response. His actions, decisions, and messaging on the topic heavily contributed to dooming his presidency, from what his pollsters later said.

Most people remember the part when he favored opening the economy, from late summer 2020 onward. What they forget are the two previous periods. There was the initial period in January, when he seemed to deny that the pathogen could do any real damage, as if he could know that. He treated the whole subject like a minor annoyance that would soon vanish (apparently, no one showed him seasonality charts from previous pandemics).

Then there was the second period in which he panicked in the other direction, from late February 2020 when he was being pushed around by Anthony Fauci and others who were pushing an unprecedented experiment of locking down the whole population to control the virus.

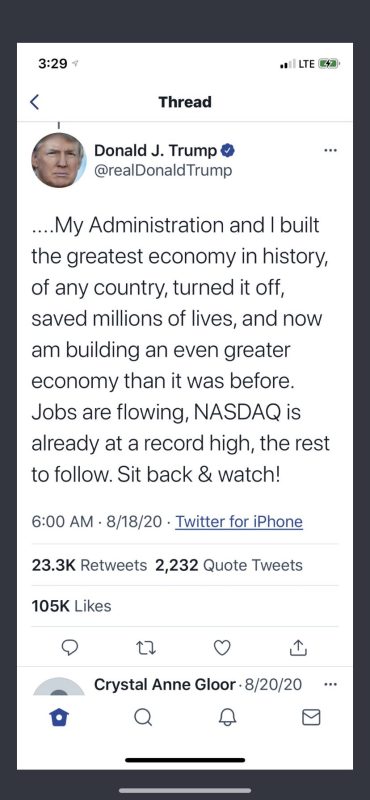

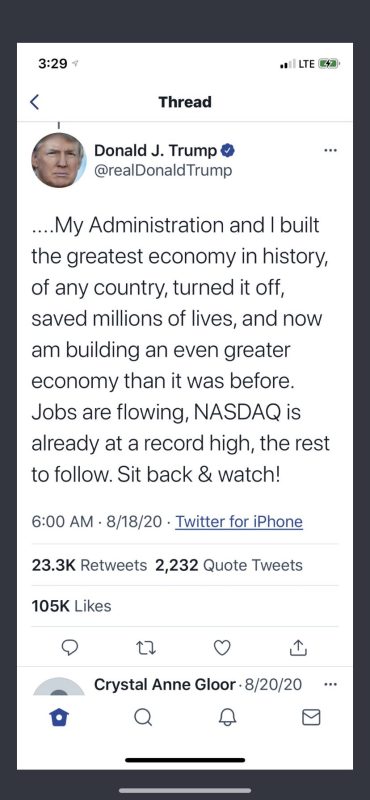

I will never forget his March 12 speech to the nation which looked like a hostage video. He ended the video with an announcement that he would block all planes from…Europe. I didn’t even know a president had such power. He later gave a press conference in which he ordered lockdowns. He defended his actions until the day he left office. He bragged about them.

VP Pence did too.

Trump even denounced Georgia for opening too soon.

The third period came many months later, long after the economy had been wrecked, the population demoralized, and his political opponents had him on the run. Out of options, he finally turned to a scientist outside of the government bureaucracy, one who had clarity of mind and the ability to communicate clear truths. He was Scott Atlas of Hoover and Stanford.

Atlas explained what top scientists around the country and the world, outside the D.C. bubble, had been saying already for months. His message was that 1) the pathogen was real, 2) it had a specific and predictable demographic impact, 3) it would cycle through the population until herd immunity made it endemic, 4) there was nothing government at any level could do to stamp out the pathogen, and therefore 5) the best approach is a public-health message to the vulnerable to shelter (and get vaccinated) while allowing society to function as normal.

Trump in these days must have become aware of his errors. And they weren’t just errors: he presided over a completely botched pandemic response. The Coronavirus issue made a mess of his presidency because he was neither intellectually nor temperamentally prepared to deal with it. If Atlas had been there from the beginning, and had been able to overrule the hacks around Trump, the history of the US and maybe the world would have been very different.

So perhaps, it was not surprising that in the last month of the presidential election, his speeches studiously avoided the issue entirely. The country was in shambles due to lockdowns but this reality did not figure into his rallies. I thought this was very strange at the time. Apart from implausibly taking credit for having saved millions of lives with his travel ban and March 13, 2020, lockdown advisory, he mostly just seemed to want the issue to go away. Covid was the elephant in the room.

So there is every reason to be curious about what he was thinking from the beginning of 2020 through the late summer when he finally surrounded himself with actual scientists without an agenda apart from reporting the science. I’ve thus far been unable to figure out what was in Trump’s head and why he made the choices he did, apart from observing that he seemed to be under the sway of a D.C. Rasputin.

Thanks to a new book coming out from Washington Post reporters Yasmeen Abutaleb and Damian Paletta – and, yes, I’m certain the book has an anti-Trump bias and probably includes many distortions – we gain some more insight into the dramatically shifting policies of the Trump administration in this extremely difficult year. He once seemed like a shoo-in for reelection; after the chaos of 2020, he fell short of victory.

In January, Trump believed Covid to be wildly exaggerated, but he still blocked travel from mainland China on Feb. 2, 2020 (but not from Hong Kong). What was he thinking? He surely knew that the virus was already in the US. The Post reporters imply that this action was an extension of his trade war and his general protectionist outlook. That theory makes sense to me. “We import goods,” they report that Trump told his staff, “We are not going to import a virus.”

Which is an interesting way to think, as if a virus is another example of the problem of globalization, a failing of too much international cooperation and trade. He never did understand trade. He could never understand the point of importing goods and services; even less could he tolerate importing a virus. His outlook on international economics might have tempted him to believe that stopping a virus would be no more difficult than stopping imports of steel.

It’s true that the flow of goods can be more or less managed through mercantilist policies, even if doing so diminishes wealth for all; it is far more difficult to do that with a virus. Even island outposts throughout the world, with an explicit zero Covid policy, have not managed to do that.

His protectionist outlook had a broader context, one of many applications of a generalized belief in his personal executive prowess and power. The dominant theme of the Trump presidency was strength in the face of America’s enemies, domestic and international. He seemed to apply that same model to an invisible pathogenic enemy. He thereby met his match.

That Trump imagined that he could somehow stop the virus is further confirmed by the following anecdote, which sounds real enough to me because it would be impossible to make up. There was a White House debate going on about what to do with American citizens who contracted Covid and wanted to return home. He didn’t want them.

From the book, we are informed that the president actually said the following: “Don’t we have an island that we own? What about Guantánamo?”

None of the data available at that time seemed to suggest that we were speaking about a plague that would kill everyone who contracted it. Studies were pouring out of China and elsewhere that suggested that this would be a widespread virus that would infect vast numbers who lacked immunity but it would only be an annoyance to most while being potentially fatal only to the very old and infirm. The demographic data on this point has been stable for 18 months.

That Trump would imagine invoking the quarantine power on that scale – creating a kind of lepers’ island offshore – indicates just how bad the information was that he was getting at the time.

In addition, that type of response touches on another bias of the president: his nationalism. Truth is that viruses pay no attention to borders at all. They don’t care about arbitrary lines on the map or voter roles or political power generally. We live in a vast world of pathogens and always have and their trajectory follows a familiar path that has nothing to do with the actions of the state managers.

Once Trump had decided that he would defeat the virus through personal strength and nationalistic policies, he had a real problem. He had to prove he was correct, simply because that’s what Trump does. That’s when the problem of testing became a major issue.

Recall that the US was very much delayed in its testing capacity, which might have been a major reason for public panic. People really wanted to know if they had it and what to do about it. There were no tests in the early days. Without that knowledge, people were left to guess. The delays in testing, which were certainly the fault of the CDC, could have been a major contributor to why things went so haywire so fast in February and March 2020.

Once testing began to be rolled out, the results revealed that infections were widespread and had been for months. Trump saw these numbers as signs of personal defeat, indicators that something or someone was mocking him. The new book has Trump on a phone call to HHS secretary Alex Azar: “Testing is killing me!” Also: “I’m going to lose the election because of testing! What idiot had the federal government do testing?”

Maybe this anecdote is true or maybe not. But it fits with the overall frame of mind that Trump took up disease suppression as a personal mission in order to illustrate his executive skill, same as he had done with making real estate deals throughout his career. No pathogen could be permitted to soil the branding of the Trump Presidency. He therefore treated the germ not as a normal part of life but an invader to be stamped out. It would make sense that testing numbers would be driving him crazy.

A final anecdote from the book illustrates the point further. He was furious when officials allowed 14 Americans who tested positive from the cruise ship Diamond Princess to return to the U.S. That decision, he reportedly said “doubles my numbers overnight.” Even though the virus had been circulating in large parts of the country for months, which he probably did not know, what drove him nuts were the optics. In the great cage match of Trump vs. the Coronavirus, Trump seemed to be losing. His answer was to double down.

The media was reveling in the daily drama, and enjoying watching Trump essentially being driven to madness, while also enjoying the soaring media traffic as a result of lockdowns. This was true since March 2020. I cannot even fathom the depths of malice that was behind anyone who hoped that this lockdown mess could last all the way into the election 7 months later. But such people were surely extant and that is pretty much what happened with the exception of a few states. Trump’s enemies had him trapped in a cage of his own creation.

The conclusion of the Washington Post book is as facile as one would expect. “One of the biggest flaws in the Trump administration’s response is that no one was in charge of the response,” they write.

No. Being “in charge” with a bad plan is not an answer. The biggest problem was an intellectual failing, and it was one shared by media elites and high-end intellectuals. They had not come to terms with the core truth that pathogens are part of the world around us and always have been. New viruses come along and their trajectory follows certain patterns. In humanity’s delicate dance with them, we need intelligence, rationality, and clarity in order to avoid the illusion of control – none of which are strengths of government.

This is why public health expertise in the 20th century always cautioned against extreme measures that cause more damage than the pathogen itself. And that highlights the single most mortifying aspect of what happened to the world in 2020: arrogance combined with ignorance blotted out all the lessons that humanity has previously worked so hard to discover and put into practice. The Trump presidency was not alone in failing the test but it was the single most conspicuous failure, one that would dramatically change the course of history.

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.