- Hospitals have always experienced surges in patient load, as long as there have been seasonal illnesses.

- Hospitals cannot pay the paychecks of their staff with constant underutilization.

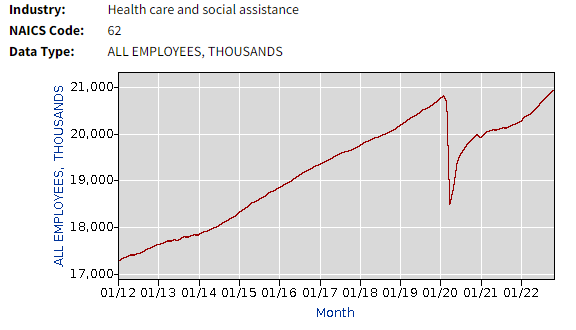

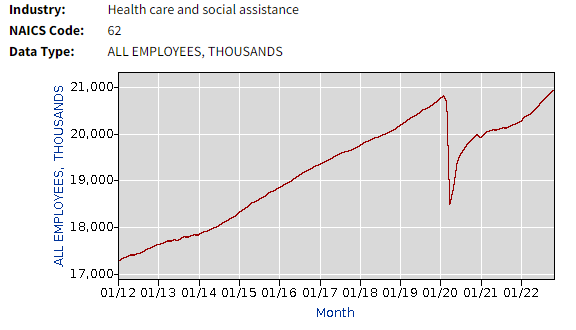

- Hospital and Healthcare clinician staffing has still not recovered to Pre-pandemic levels or trends.

- Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, media coverage (though predictably alarmist), made no suggestions of government-mandated citizen behavior change because of hospital capacity.

- Second-order effects of alarmism harm patients.

- Data regarding Hospital utilization is public and easy to access, making it easy to fact-check claims from media and social media pundits. (Skip to the dashboards here and here)

Before the flatten-the-curve movement, the media reporting on this issue took a slightly different tone. Primarily, the coverage lacked any kind of moralizing or value judgements about human behavior.

Take this article from NPR in 2015, for instance. The overall tone is one of readiness, and the premise of the article is that building capacity is in response to a potential need. Another article from Time in 2018 documents cases where hospitals were “overwhelmed” throughout much of the country during a flu epidemic.

The only behavioral changes referenced by doctors in the article was to get a flu shot, and use their primary care provider, and not the ER for treatment. A New York Times article from 2018 discusses the surge in flu patients rather benignly, treating it as predictable and well-known phenomena.

An article from CTV News press in 2013 manages to address the surge without demanding systemic government intervention. A Globe and Mail article from 2011 even referenced public health officials concerned about “hysteria” among the public and the potential negative consequences, namely how it leads to reduced flu shot uptake.

Let’s contrast that with recent coverage of hospital capacity. Of course, during the early days of the pandemic, we all saw the scary projections about capacity overruns, and the “flatten-the-curve” charts. Then we saw what actually happened – a typical respiratory virus wave, out of the typical winter season, that happened at different times in different areas.

In the Spring of 2020, aside from key areas, most hospitals did not experience a surge. The postponing of “elective” surgeries (financially essential for hospitals to stay afloat), actually led to massive layoffs, and the healthcare and hospital employment sector has yet to still fully recover from it.

Notice the trend in years leading up to the pandemic. With a Boomer population aging, it’s important to realize that we are still barely back to pre-pandemic level staffing, when the pre-pandemic trend shows we should be higher by now.

While we were all led to believe that the surge would be catastrophic, there was little coverage of the fact that hospitals already had playbooks for this. This HHS Document for planning for surges, first published in 2018, details all of the logistics involved in expanding capacity when patient load is higher.

Diversion, which is when an Emergency Department has to divert incoming ambulances due to not having capacity, happens regularly during non-epidemic times, up to 33 percent of all hospital days according to one study. The CDC publishes a “FluSurge” planning tool for hospitals to plan for surge periods. The whole concept of surges was fully acknowledged and planned for, yet this was largely ignored during the spring of 2020.

In March 2020, The American Hospital Association even sent a letter to Jerome Adams, then the Surgeon General, assuring him…

”Hospitals, working side-by-side with their physician partners and other caregivers, will continue to provide needed care and procedures where it is safe to do so, prioritizing care that, if delayed, could negatively affect the patient’s health outcome, harm the patient, or lead to disability or death.”

Despite all of the hysteria never materializing into the crisis that was predicted, we still see media articles fear-mongering about hospital overruns and being “overwhelmed.” Even worse, we still have Dr Adams himself (no longer Surgeon General) tweeting out alarmist takes like this:

Notice that he mentions no specific hospital, uses subjective language (“breaking point”), and even goes so far as to tell heart patients to forget about seeking care. Chest pain? Sorry folks, we’re full. What is the potential effect of telling a heart patient this news?

Well, we don’t have to guess. We know that during the initial lockdowns, there was a change in care-seeking behavior for those experiencing heart-related symptoms which led to increased heart related mortality.

“The [acute myocardial infarction] fatality rate during the pandemic remained significantly higher than in 2019 even after excluding patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection.”

“Stay-at-home mandates and fear of catching the virus in the hospital setting are likely to have discouraged access to emergency medical services in COVID-19 hotspots. Furthermore, the relocation of health-care resources to prioritize patients with COVID-19 might have contributed to deferred treatment of less urgent cases of STEMI.”

What changed? How did we go from a media that correctly covered the counterproductive role that hysteria plays, to a full-on embrace of constant hysteria, even after we’ve successfully weathered two respiratory virus seasons?

The 2020 “flatten-the-curve” movement seems to have conditioned a significant portion of the public to the idea that human behavior could or should be curbed to preserve arbitrarily-defined “healthcare capacity.”

Embedded within every assertion that we must curb human behavior to preserve hospital capacity is that somehow someone who is presumably in charge of planning and implementing hospital capacity actually knows the exact correct answer as to how much capacity should be.

What if they’re wrong? The very concept of “capacity” presumes that we have certainty about things that we do not. As we see from the BLS data above, our efforts to preserve capacity paradoxically ended up in the largest drawdown of healthcare capacity ever seen.

The common thread among all of this coverage is that they all focus on the system, rather than the human. There’s this concept called “capacity” that we all somehow need to know about, and we all need to make decisions because of it.

The entire concept is backwards. It’s a fundamentally utilitarian mindset that stems from a fundamental misrepresentation of how systems work, and an inverted moral philosophy that prioritizes systems over people. Hospitals were built for humankind, not humankind for the hospital.

Even after almost 3 years of the “flatten-the-curve” craze that shut down the world, Anthony Fauci continues to falsely claim that we “were seeing hospitals overrun.” He then goes on to defend lockdown as an appropriate tool to use. Pay attention to his language; he presupposes the power to lockdown exists, then tries to downplay it as “only a temporary issue.”

We know from recent history that this is just brazenly false, that outside of his fantasy-land head, lockdowns were very prolonged in many countries throughout the globe. It’s really incredible that we’re still hearing the most influential man in public health make statements like this, well after lockdowns and other futile efforts to “stop spread” have proven failures.

Some honesty

While the media does what the media does – drive clicks to sell ads – if you look for it, you can find honest and realistic takes, like these, which were in response to Former Surgeon General Adams’ tweet from above:

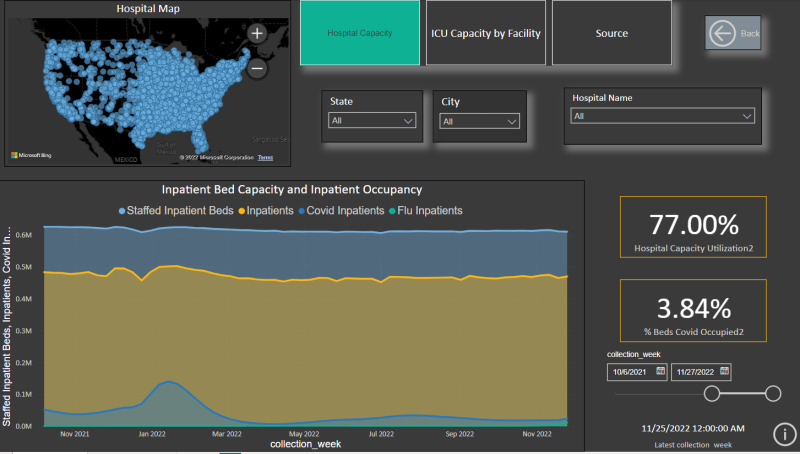

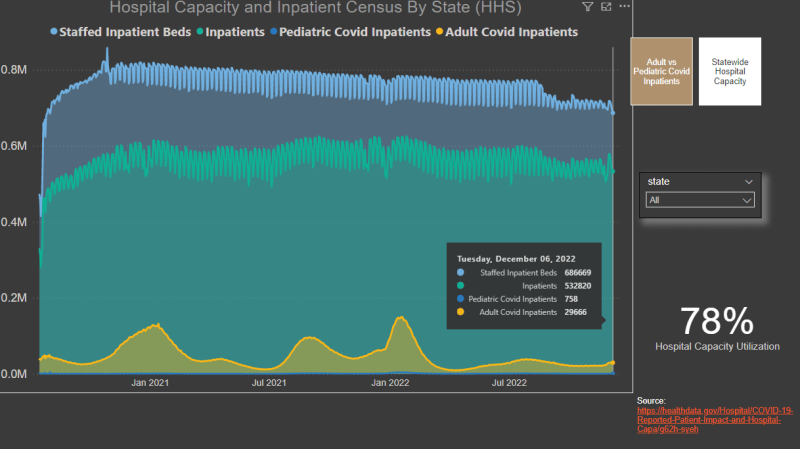

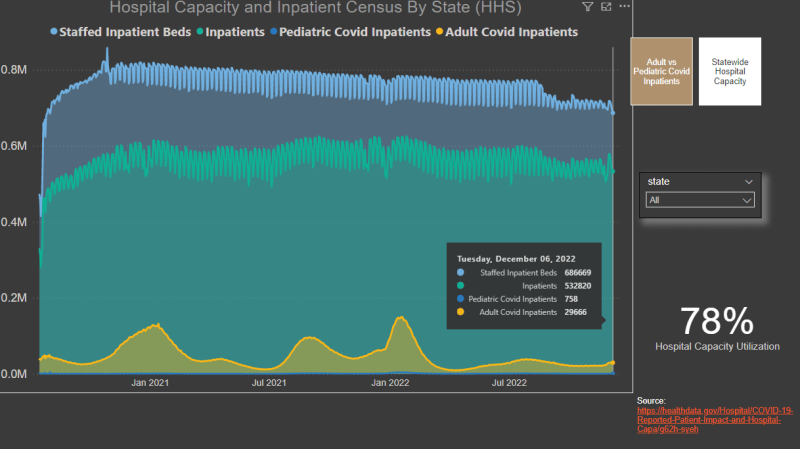

Finally, you can take a look at HHS’s public data reporting on facility-level capacity at the below dashboard. These data are reported as 7-day averages, so intraday level numbers will be smoothed out. This is meant to provide as accurate a picture as possible about what is actually happening with hospitals across the country.

Disclaimer: this dataset’s totals will not match the HHS state level’s data exactly, as HHS’s facility level data does not include every hospital (last I checked it included ~95% of them). The data is meant to show trends and overall percentages of capacity used. Individual level hospitals’ data will be as accurate as their reporting is.

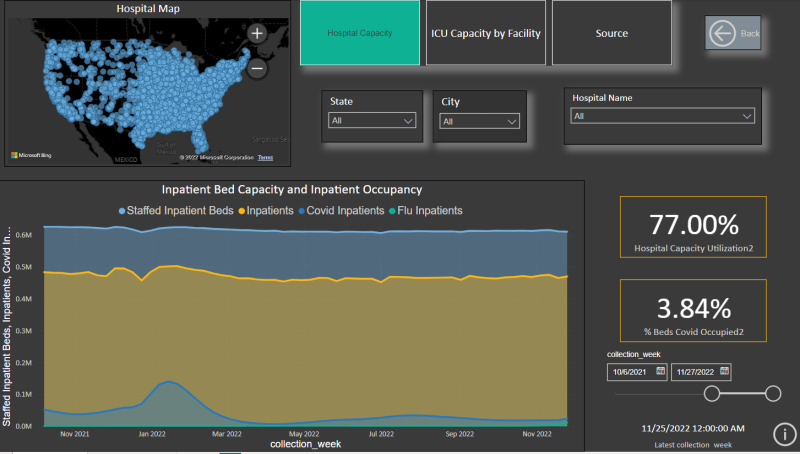

For State-level data and daily Inpatient census numbers, you can review the below dashboard, which is visualized from HHS data. It’s pretty interesting that you can actually see the holiday effect when it comes to patient census. Turns out that clinicians like to take Thanksgiving off too. You can see the reduction in patient census during the Thanksgiving holiday weekend.

The next time you see your local churnalist cranking out another Sky Is Falling article about hospitals being overwhelmed, feel free to use these tools to check whether or not there’s even a kernel of truth to it.

Reprinted from the author’s Substack

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.