A good education prepares one for the realities of adulthood and successful interaction with the world. At the university level, whether via college or homeschooling, a good education develops the intellectual, emotional, and social muscles. One is moulded into a person who uses tools, not crutches; who accepts responsibility rather than accepting stories of victimhood; and who recognises that human flourishing happens in communities, not in isolation.

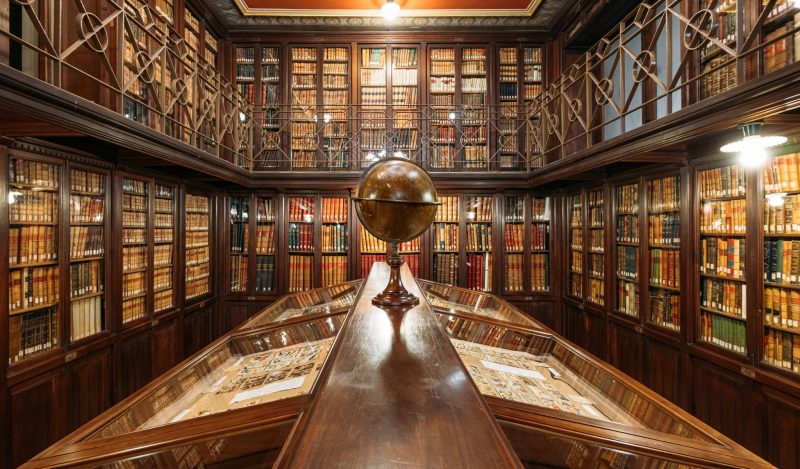

Good education at the tertiary level was delivered for 500 years by small independent colleges offering an immersive campus environment in which the development of all muscles accelerated. Immersion, reflection, and personal feedback delivered in a small, self-contained community were the norm for the elite.

We ourselves have enjoyed the best of the system as it was in the late 20th century, from European gymnasiums to the American Ivy League. Indeed, our generation has the highest average IQ of any generation in the West.

By contrast, newer generations have regressed to cognitive levels not seen for a century, with sharp declines at the top end: average mathematics scores have dropped, and attention spans are particularly reducing for the young, from over half an hour to under a minute. The abilities to focus, to think critically, and to be socially resilient have declined spectacularly over the past 50 years. Studies suggest strongly that the average IQ in Western countries, after steadily increasing during the 20th century as more people got access to better education, has been falling for the past few decades.

The reason for this disastrous decline is not genetic. The reason is that what made us smart is no longer working. The probable causes are smartphones, addictive internet distractions, bureaucracy, bad social habits, and incessant disruptive propaganda, all of which have permeated higher education institutions and the lives of those who attend them. The corollaries of these phenomena have degraded what is still sold as elite education, through constricting and bogging down all core functions while simultaneously altering the composition of the student body.

Principles of Reform

Three main principles suggest themselves to guide the way forward.

The first solution principle is to deliver higher education once again in a small and independent format. This requires eliminating the layers upon layers of bureaucracy that encrust our modern institutions of higher learning, as these layers rob academics and the institution as a whole of independence, including the freedom to deliver transformative education.

As an indicator of the enormity of this problem, consider that in six of the eight ‘best’ Australian universities (collectively called the Group of 8, or ‘Go8’), administrative staff outnumber academic staff, and not by a small margin. Since the mid-1990s, non-academic staff numbers have grown at a rate 70% faster than academic staff. In the US, the situation is the same: Yale, one of our alma maters, has more administrators than undergraduate students, and it is not exceptional.

Bureaucracy infantilizes students and academics. Bureaucracy is naturally antithetical to immersive or inspirational education because it is oriented towards processes, not students. Telltale signs of bureaucratic takeover in a higher education institution are prescriptive learning outcomes, take-home exams, ‘safe spaces,’ enormous lecture halls, permission forms, and special needs programs. One must escape from large universities and from the grasp of state education authorities whose regulations demand ever more bureaucracy to ensure compliance and thereby force one back into mediocrity.

Bad social habits, smartphones, and addictive distractions form their own challenge. The living environment in many universities today contains friends who expect one to be available all the time; fast food that tastes good but leaves one fat and cranky; and easy digital access to porn, puzzles, games, and social titillations, all seducing the young with quick dopamine hits at the expense of their longer-term development.

Since the biggest temptations are around our desire to be part of our group, the second solution principle is for top-flight tertiary institutions to explicitly engender new group habit formation. The environment must be so immersive and potentially socially rewarding that students are motivated to explore and discover better social habits with each other.

An outside world full of incessant, deliberate, personally tailored, disruptive propaganda forms the biggest challenge, one that the colleges of old did not face because manipulation was then not so well-organised, constant, and immersive. It was easy before 1970 to keep the rest of the world away from the learning environment.

Any person with a smartphone today is now nudged daily to believe in a new enemy, a new quick fix, our own undoubted greatness, the infallibility of a leader, and a new obsession. All of our weaknesses are brutally explored and abused, via manipulation now done fully automatically by algorithms that know us better than we know ourselves. Against this onslaught of intelligent manipulation of all our weaknesses, there is only one means of escape: we must face and own our weaknesses courageously, transforming them into opportunities for personal development.

To equip students with the ability to thrive in a world where their deepest fears and desires are constantly weaponised to manipulate them, the third solution principle is to practice radical honesty about ourselves and human society.

We expand on these three solution principles below, showing how they point to a completely different form of academia from the one we currently have. Hardly anything in the education market today is aligned with these three principles, so either we are wrong, or the market is yet to develop. (No prizes for guessing which of these we believe is true.)

Small and Independent

Small, independent colleges have huge cost disadvantages over the current degree factories. In a small place, the staff-to-student ratio is much higher, the quality of the staff must be better, and the college must do all its own overhead (IT, grounds management, marketing, staff recruitment, HR) for a community of students that is easily a hundred times smaller than the present norm. The first such pioneering small independent colleges, which cannot scale activities like marketing and IT, face a mountain to climb – a massive barrier to entry, in the lexicon of economics. That is partially why they do not yet exist.

Is this ‘small and independent’ principle really necessary? What hurdles do super-rich, medium-sized places like Harvard and Yale face that prevent them from offering top-flight education?

The Achilles’ heel of the Ivy League colleges in America, and similar places elsewhere, is their large bureaucracy that, while handling the IT, marketing, recruitment, and all other overhead activities, does so at the price of continually finding problems for which the solution is more bureaucracy and less learning. This is the nature of a large bureaucracy. On top of this, bureaucrats’ ears are tuned not to academics but to government requirements and to threats of legal claims. Perhaps most insidiously, their jobs rely upon formalising and standardising the education experience, and in the process, students’ money, time, and attention are sold off to commercial interests.

Let us suffice by illustrating the last, most contentious point: the selling of students’ resources, which is achieved in several insidious ways in the Ivy League and other allegedly top institutions of higher learning.

Consider first the capture of both curriculum and pedagogy by commercial interests. It is standard today for a university to subscribe to a “learning management system” (e.g., Canvas, Moodle, Blackboard) that sets out a formal structure for organising what is done in a course. The initial decision of which system to subscribe to is often lengthy and somewhat competitive, but once a decision is made, a university is essentially stuck with one technological “solution,” which shoehorns academics into using that system as well.

What they teach and the way they teach it is then immediately more prescribed, more planned in advance (and hence less able to be adapted to students’ needs as a course proceeds), and more on display – meaning more auditable by bureaucrats looking to compliance-check – than in prior eras, while bugs in the system inevitably emerge and get addressed only slowly and half-heartedly because the university’s costs of switching to another system are high once they have signed on the dotted line.

The formal structure forces students’ time and attention to be directed towards the learning management “solution” itself, bugs and all, and whatever features or packages are easiest to use within it, from specific plagiarism-checking software to particular file types. How convenient for Adobe, Turnitin, and many other companies that thereby get free advertising and pressure on students to use their products.

Additionally, various accepted ideologies are infused into the modern curriculum (think climate change, gender fluidity, or the exaggerated threat of Covid) that sound good to bureaucrats and are useful for companies looking to find their future clients. Pharmaceutical companies’ interests drive what is taught in medical schools, with a Harvard Medical School academic and former editor of the New England Journal of Medicine opining more than twenty years ago that “[w]hen the boundaries between industry and academic medicine become as blurred as they now are, the business goals of industry influence the mission of the medical schools in multiple ways.

In terms of education, medical students…under the constant tutelage of industry representatives, learn to rely on drugs and devices more than they probably should.” Imagine how much worse things are now, twenty years on. The same corruption of the curriculum has occurred in other disciplines, like mining and food science, where commercial interest in gaining students’ attention is high and bureaucrats can require that certain “standard” content is covered.

Another hijacking of students’ resources occurs when students’ time is taken up by learning ever more specialised commercial software (in economics, the most common are Excel, Stata, SAS, Matlab, and EViews). University bureaucrats are more than happy to hook their own students into this software, even pointing out the use of such software as an educational benefit, arm-twisting them to be future clients. Instead of becoming masters of the ideas behind techniques, students are led to be slaves of the companies making money from techniques.

A deeper hijacking takes place at the level of preferred theories of the world that suit the powerful. Students are taught in mainstream economics programs that, with few exceptions, those who are rich deserve their stations, having earned them through the operation of healthy market forces rather than through the corruption and grey gift exchange that in fact are the engines of wealth accumulation in many parts of the modern West.

Similarly, students are encouraged to be antagonistic to each other: the lesson that the enemy is within their own ranks rather than external to them is underscored through the (again bureaucracy-approved) incessant harping on about entrenched within-group conflict, such as domestic violence and systemic racism.

The real enemies of societal health, including the corrupt elite and the huge multinational companies that many of them run, are quite happy with this state of affairs, for obvious reasons: it weakens resistance to their will while creating an eager new generation of buyers.

We can see this shift in focus by comparing modern university mission statements to ones from prior years. As recently as 2014, Harvard’s mission statement read as follows:

“Harvard strives to create knowledge, to open the minds of students to that knowledge, and to enable students to take best advantage of their educational opportunities. To these ends, the College encourages students to respect ideas and their free expression, and to rejoice in discovery and in critical thought; to pursue excellence in a spirit of productive cooperation; and to assume responsibility for the consequences of personal actions.

Harvard seeks to identify and to remove restraints on students’ full participation, so that individuals may explore their capabilities and interests and may develop their full intellectual and human potential. Education at Harvard should liberate students to explore, to create, to challenge, and to lead.

The support the College provides to students is a foundation upon which self-reliance and habits of lifelong learning are built: Harvard expects that the scholarship and collegiality it fosters in its students will lead them in their later lives to advance knowledge, to promote understanding, and to serve society.”

Today, Harvard’s mission statement is the following:

“The mission of Harvard College is to educate the citizens and citizen-leaders for our society. We do this through our commitment to the transformative power of a liberal arts and sciences education.

Beginning in the classroom with exposure to new ideas, new ways of understanding, and new ways of knowing, students embark on a journey of intellectual transformation. Through a diverse living environment, where students live with people who are studying different topics, who come from different walks of life and have evolving identities, intellectual transformation is deepened and conditions for social transformation are created. From this we hope that students will begin to fashion their lives by gaining a sense of what they want to do with their gifts and talents, assessing their values and interests, and learning how they can best serve the world.”

What is gone? The non-specific creation of knowledge, the non-specific opening of minds, respect for ideas and their free expression, discovery, critical thought, the non-specific fulfilment of potential, exploration, challenge, rejoicing, personal responsibility, and self-reliance. What has taken its place? Diversity, personal identities, personal wants, values, and interests, and the specific goals of intellectual and social transformation. What is held up as the goal is learning by and for particular pre-known phenomena (“diversity” and “transformation”), in a way that caters to self-interest and adheres to buzzwords that look good on a marketing brochure.

The degradation of what happens at universities has occurred with the complicity of academics themselves, who often find it in their own career interests to go along with mainstream ideologies, and too hard to resist the bullying by the bureaucracy to do so at other times, leaving no one to protect the minds of students. It is academics who have sold the students to the pushers of harmful substances and stories, whether that is pharmaceuticals, the woke brigade, or the food industry. ‘We’ invited those pushers to design our curricula and educate our students, or, for the right price, we inflicted their propaganda ourselves.

It’s a lucrative gig. We – both the individual academics and the institutions we work for – get a good price for selling out our students: research grants and general admiration for the academics, endowed buildings, and a seat at the top table for the bureaucrats. The students, not knowing they have been sold out, do not complain either, as they believe they are getting the best education possible, guaranteeing them a good job when they graduate.

It’s all win-win, except for the futures of the students and society at large, as dumb sheep flood the labour markets and the polling booths. Instead of mature, thinking individuals aware of real-world dangers who feel a personal stake in protecting and building their communities, we get selfish sub-adults with no interest or ability in forming thriving organisations.

As Elon Musk said recently about the economic cheerleader of the Trump tariff war, Navarro, an economics degree from Harvard is a bad thing, not a good thing. This was of course already clear to Brownstonians from the fact that none of the supposed top 50 US economists opposed the Covid lockdowns when they were asked to comment on them in April 2020.

Elon has noticed too, and is simply being unusually honest about the true state of quality of the Ivy League. He is saying what the captains of industry already know, but will still take a while to trickle down to the ears of rich families: the Ivy League is no longer in the business of offering top-flight education, nor can they be while they are so bureaucratic and beholden to corporate interests. Expanding and systematising their education offerings has destroyed them, leaving the supposedly top places without the right students, the right curricula, or the right academics.

One needs to be small in order to avoid having a large bureaucracy. One needs to be independent from money in order to avoid selling students’ resources. Together, these requirements imply that one needs to be outside of the government accreditation system in order to escape the tentacles of official bureaucracy. Ethics committees, the directions of politicians, compulsory learning outcomes, health and safety regulations, and so forth are terms by which government bureaucracy will force any college working within the system to surrender their students to propaganda and commercial interests.

We conclude that ‘small and independent’ is a true imperative. To rediscover good tertiary education, we must return to the model of small, independent colleges that delivered such education for most of the last 500 years. Colleges no bigger than a few hundred students should once again become the norm at the top end, as they were until the 20th century. The top will have far fewer administrators, and also far fewer students.

New Group Habits

The problems of bad social habits, smartphones, and addictive distractions are tough to crack, particularly as they become ingrained so early in childhood by parents who employ digital devices and junk food to sedate their children the minute they’ve spat out their pacifiers. Bad social habits include a ream of dysfunctions like poor diet, poor exercise habits, pervasive victimhood mentalities, unhealthy gender relations, and an absence of personal responsibility.

Only very few of today’s adolescents have been lucky enough to go to schools and be in families that have avoided these bad habits. The rest eat poorly, exercise little, have gotten used to being treated like helpless morons and are lost if they are not treated this way, cannot relate healthily with the other sex without huge amounts of alcohol, and have learned dependence on this situation by being accorded some form of victimhood.

One might think the solution is to ban modern technology from schools and colleges, but alas: even those few students who have resilient families and communities behind them have a social life and self-image of which both are largely online and maintained via smartphones, which subjects them to continuous temptation. Pornography, grooming, online games, relentless marketing, emotionally appealing political propaganda, clickbait, social pressure to seem a winner at all costs, and the infinite memory of everything embarrassing one has ever said – all this is waiting to ambush a student every online minute. Only superhuman adolescents can be immune on their own, and any simple ban will be evaded by smart young people.

These technologies are not easily discarded for the additional reason that graduates must be ready to use them if they wish to be successful in the world, as the world of work and social connections forces one to be online and on the phone. While one can reduce exposure using various tricks, one cannot simply shut out modern personal technology entirely and hope to continue to be part of modern society. Yet, through this technology, students are at the mercy of those with the money to determine what they see and consider. Letting technology in, therefore, also means dealing with deliberate and constant intrusive propaganda.

The challenges of bad modern group habits for tertiary education design have not been fully taken up by any existing university or college. Partly this is a failure of the academics to face the problems that students face: having already ‘made it’ ourselves when the world was different, we prefer either to ignore students’ modern problems or make them worse by embedding them in the learning process. As for university bureaucracies, they scarcely even recognise these as problems they should try to solve.

The challenges of bad habits, digital devices, and perpetual exposure to the internet were not around previously, so we cannot look to the past for solutions. So, how do we deal with them?

A New Model

One approach is to set up a socially experimental campus environment in which students themselves must discover how to be a community with each other, working through the problems they come in the door with, including bad habits and dysfunctional gender relations. In this environment, the students themselves must figure out collectively how to avoid the distractions of digital devices and social media by exploiting the social possibilities right in front of them: each other, in person. Achieving progress on this front will take real conversations and a willingness to experiment and make mistakes.

Students can, for example, design their own speed-dating session to figure out who is somewhat attracted to and interested in whom, much like village squares have been used for centuries for this purpose. Students can negotiate healthy food and exercise regimens with each other, on the basis of their own joint research. Students can figure out how to make space for more socially awkward members who do not want to socialise much. Students can figure out norms for when to all stay away from smartphones and when to all make time for them. Students can figure out what to do with members who cannot resist the temptations. In truly honest conversations with one another, students can work these and other things out as a group.

However, honest conversations themselves are not the norm in modern society, so they need to be practised and habituated to. Students can be helped in this to some extent by academics and alumni, who can suggest tricks to arrive at honest conversations, but at the end of the day the chasm between what is healthy and the social habits that are now normal is so huge that the leap can only be made by the students themselves after honestly facing those problems and taking responsibility for their solutions. This will be quite difficult, risky, and stressful, so it is something that no large bureaucracy can steward.

While pushing away the bad side of new technology, how does one capture the good? Our suggestion is to be academically experimental when it comes to AI and other new technologies. We advocate trying new technology and then jointly evaluating its usefulness with students, gradually homing in as a collective on what works best.

For example, guided by the principle that AI should help students hone their mental muscles rather than replace their own thinking, a learning collective might hit upon the idea that it is necessary to encourage students to use AI in a healthy manner. One might try to do this by calling them out quickly when they falter by using AI as a crutch rather than a tool.

The energy to do this cannot come from the academics alone, as their time is limited, and also because an individual’s degree of motivation for proper use is social in origin: students follow their peers as much as they do the academics. So, it is students who must help each other to use AI for the better. Habits of work and peer discussions must be found that make healthily AI-augmented learning fun and rewarding.

Take, for example, the use of AI in helping people become better writers. AI gives reasonable feedback on grammar, sentence structure, paragraph transitions, and the correctness of certain ‘facts.’ Yet, the temptation is for a student to ask AI to write a whole initial text and then adjust it sufficiently to make it seem plausible that it was written by the student.

Over time, indulging in that type of use destroys the student’s creativity, as his or her writing muscles do not get stretched. How does one get students to avoid that trap, while still being close enough to AI that they practice writing while using AI to provide feedback at the right moments?

One possibility is for students to write individual initial essays with pen and pencil for an hour or so in a communal space in which ‘AI cheating’ would be observed. After that hour, they would present and discuss their essays to each other in one-on-one conversations. This would help to weed out those who lapsed into having AI do their work, because their discussion partner would notice. They could then improve their essays based on the feedback provided by their partners, and only then would they turn to AI to suggest ways to improve the grammar, the paragraph flow, or other structural elements.

Such experimentation could be done in large universities, but bureaucracies would be dead set against it because these kinds of activities are by design unmonitored and rely on strong social communities of students and academics who are in the habit of helping each other. To a bureaucrat, that all spells potential litigation, loss of power, and indeed possibly even loss of a job. Nothing to gain, that’s for sure.

Small colleges are the only places that can become the experimental laboratories required for social and learning communities to (re-)discover and develop new social habits. They are places where solutions to modern technological challenges and opportunities can be discovered. Top young students are needed to do this, precisely because they have the most to gain from figuring it out: they can individually and as a group best see both the solutions and how to ‘sell’ these solutions, once they graduate, to the rest of society. Their solutions can trickle down to businesses, secondary schools, and whole communities. Their solutions become societal solutions: the result of pursuing personal interest becomes a form of assistance to their country.

A Final Feature: Radical Honesty

As impolite as it is to say so, Machiavelli was right 500 years ago. Nietzsche was right 150 years ago. Social psychology and neuroscience are right today: we humans lie to ourselves continuously, particularly when it comes to social matters. We flatter ourselves and our bosses. We believe authority because that gets us into less trouble. We go with what is easy in the hope of avoiding effort. We go with the easy explanation just to have an opinion. We lie because trying to discover or face the truth is such hard work.

Lies to ourselves and others are an incessant feature of the landscape, and intellectuals lie more than others because it is particularly hard to catch them out. As the old quip goes: “Some things are so stupid, only an intellectual can believe in them.” We have seen this truism in action over the last five years during the lockdowns, the mRNA vaccine mania, the onslaught of woke, and so forth: the intellectual class in particular lied and lied and lied, both to themselves and others, because it was easy and because they truly were clueless.

The internet and modern media are manipulation machines when it comes to anything commercial and controversial, essentially aiming to rob us of whatever we have: our money, our vote, our youth, our time, our bodies. What they manipulate most of all are the lies we tell ourselves: what we lie to ourselves about is quickly recognised by automated programs, and then weaponised to fleece us. It is an industry now.

If we are dishonest about our own ignorance of crypto, an AI will send us an ad to trade on crypto exchanges, promising we will get rich quickly while quietly charging us fat commission fees. If we are dishonest about our talents, an AI advertisement will flatter us and get us to apply for jobs and partners we have no chance of ever getting, increasing the number of hits on the right websites.

If we are dishonest about our own social inadequacies, an AI-guided advertisement will tell us we have a well-recognised mental disorder which gets us off the hook and for which we should use the appropriate expensive medication. If we are dishonest about our secret fears, an AI will push us towards buying something that will avert the danger we fear or push us towards voting for the guy who will avert the danger.

In this strange way, our lies are now punished nonstop by algorithms. Our lies have become our weaknesses. This is not going to stop after we emerge from an educational institution, or in ten years’ time. The manipulation of our weaknesses is now a reality 24/7, for the rest of our lives and those of all our students. Soon AI will arise that is much better than humans in recognising our weaknesses, punishing us ever more for them.

In the face of this reality, we have to do something we have never truly done before in the history of education: adopt a practice of radical honesty-to-self-and-society. Only honesty to self can protect one from the temptations of propaganda, advertising, and lazy answers that the modern world offers in spades. Only honesty to society can help lead others towards being less manipulated.

Honesty to self is painful. Machiavelli thought that almost no one could do it. Nietzsche was so despondent about people that he called for ‘uber-mensch’ who would set themselves this near-impossible task.

Yet, self-honesty is a muscle that can be trained and developed. To grow, it needs emotional safety and an environment in which others are growing in this dimension, too, but it can be done. Both Machiavelli and Nietzsche gave us books that illustrate what radical honesty looks like: both said things that were despised by the mainstream throughout the ages, but like any unwelcome truth, their messages keep coming back.

Machiavelli told us that most people judge on appearances because they lack the understanding to analyse actions, that rulers have to maintain fear stories in order to rule well, and that people will forgive others more easily for killing their fathers than for taking their inheritances. These are terribly unwelcome messages. Who would not wish for these things to be untrue? No wonder that Machiavelli has been denounced by all and sundry.

Yet, if true, think of the damage AI manipulation can do to us by nudging us to continue to ignore such truths: we would continue to be led by appearances, manipulated by our fears, and wrong about the actions of others that we will be resentful about. Accepting that he might be right is a first step towards discovery of self and society.

Nietzsche was even more brutal and confronting. He told us all humans had a ‘will to power’ and that to grow, one needed to accept this about oneself, working with it rather than pretending to be able to let go of it. He also argued that reason ‘killed god’ and that humans needed to find god in themselves. He thought modern society was inherently soulless and consumerist, cut off from god, as in a market, god gets degraded into yet another beggar looking for cash. He wanted humans to find faith within themselves, via continuous self-challenge and external works.

How horrible and confronting! Who would wish to face such possible truths, once one realises what they imply about how one has lived until now? Just reflect on what ideas like that do with the world of ‘safe spaces’ or the notion of ‘the pure of heart’: they expose the first as infantilising and the second as pure deceit. Yet, again, tough though the message is, it is soulful and in an unusual way, liberating. It offers avenues for individual and societal growth.

Both Machiavelli and Nietzsche argued that the scholars of their time were solidly engaged in propagating various ideological lies in their ancient colleges. As noted above, Nietzsche thought scholars were responsible for killing god. Machiavelli humorously noted that practically all scholars he knew were busy ‘thinking up worlds that never were and will never be,’ implicitly accusing academics of hiding from reality rather than facing up to it. Their thoughts echo what we have seen from most of those calling themselves academics in our own time.

Nevertheless, both men loved their society and wanted to help that society, lying manipulators and all. They went through the looking glass, first recognising their and others’ nature, and then accepting that nature and working with it rather than against it. They were trying to be radically honest. This radical honesty is also what is needed to protect against constant manipulation: immunity is provided by the lack of something to manipulate. As Socrates, another rebel, famously opined: true knowledge begins with self-knowledge.

The final challenge of helping students to be true to self – to see themselves, others, and society honestly, yet not dismissively – is a Herculean task that requires a stimulating, confronting, inspiring, and intellectually unforgiving environment. Living in such an environment, in turn, can only be managed for a human being if the environment is also emotionally warm, forgiving, and spiritually nourishing. The growing pains of radical honesty need the balm of joyful kindness.

In summary, the future of top-flight tertiary education is radically different from what we now have in the Ivy League and the old prestigious universities of Europe. Existing elite institutions have abandoned their missions and souls by becoming big and bureaucratic. They are now incapable of fulfilling their old missions, let alone providing solutions for the new problems that smartphones, the internet, massive government bureaucracy, and incessant manipulation have brought.

To realign tertiary education with its classic mission, we advocate a return to small campus colleges and the creation of environments in those colleges that are socially open, technologically experimental, and radically honest about humans and our society.

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.