Across the world, thousands of pregnant women are being prescribed antidepressants. Yet few are warned about the potential harms to their unborn babies.

That concern came to the forefront at a 2-hour expert panel convened last month by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), moderated by Dr Tracy Beth Høeg, the agency’s senior adviser for clinical sciences.

A lineup of doctors, scientists, and former regulators gathered to examine a thorny question: do selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) cause more harm than good when used during pregnancy?

Their opinions were not unanimous, but all agreed on one striking fact—there are no “gold-standard” randomised trials that have addressed the issue.

Instead of sparking serious debate, the panel was savaged by the media. The ferocity of the reaction only highlighted how difficult it has become to speak honestly when the message challenges psychiatric drugs.

A Long Overdue Discussion

FDA Commissioner Dr Marty Makary opened the session with a stark warning. “We’re losing the broader battle of addressing mental health in the United States,” he said. “The more antidepressants we prescribe, the more depression there is.”

He cautioned that serotonin plays a crucial role in foetal development and warned that SSRIs have been “implicated in postpartum haemorrhage, pulmonary hypertension, cognitive downstream effects in the baby, as well as cardiac birth defects.”

Dr Anick Bérard, an epidemiologist at the University of Montreal, said “depression and anxiety in pregnancy is extremely prevalent” and warned the problem surged during Covid-19.

“Since the pandemic started, the prevalence of depression and anxiety in pregnancy more than doubled. It was close to 25 to 30% at the peak of the pandemic,” she said.

“Six percent of pregnant women will take an SSRI at one point in time in their pregnancy,” she added.

Bérard cautioned that “using SSRIs is not the miracle solution in the sense that 12% of women that are using SSRIs remain depressed in pregnancy.”

Birth Defects

Maternal–foetal medicine specialist Dr Adam Urato was unequivocal. “Never before in human history have we chemically altered developing babies like this…and this is happening without any real public warning,” he said.

Urato told the panel that patients are routinely misled.

“The only counselling they received is that SSRIs don’t affect the baby or cause complications. This is simply not accurate or adequate,” he said, adding that FDA labels fail to warn about harms such as preterm birth, pre-eclampsia, or the fact that SSRIs alter foetal brain development.

Published research has raised similar concerns.

A BMJ study found birth defects occurred 2 to 3.5 times more frequently in babies exposed to paroxetine or fluoxetine early in pregnancy. A JAMA Psychiatry study found venlafaxine was associated with the highest number of defects. And a 2018 meta-analysis covering more than nine million births found a modestly increased risk (11%) of congenital malformations linked to early SSRI use.

“SSRIs cross the placenta and enter the foetal brain,” Urato explained. “These drugs alter the mom’s brain. Why wouldn’t they affect the babies?”

He pointed to ultrasound studies showing SSRI-exposed foetuses with “different movement and behaviour patterns,” and noted that newborns can present with “jitteriness, breathing difficulties, and higher rates of admission to the neonatal intensive care unit.”

By his count, “a dozen consecutive MRI studies” now demonstrate that prenatal SSRI exposure alters the developing brain.

Tapering Hardly Discussed with Pregnant Women

Dr Josef Witt-Doerring, a psychiatrist and former FDA official, said women often come to him unaware of the risks. “They’ve never heard of these things,” he said. “And they feel incredibly betrayed.”

He helps patients taper off psychiatric drugs, but warned, “There’s a black hole of knowledge on how to taper these medications.”

He suggested practical improvements, such as QR-code based videos on pill bottles, to give patients and physicians accessible, real-time guidance.

That concern is underscored by a 2021 meta-analysis, which reviewed 13 studies and found that up to 30% of infants exposed to SSRIs in the womb developed withdrawal symptoms—tremors, muscle tone abnormalities, rapid breathing, and respiratory distress—while unexposed infants showed none.

The authors concluded that “tapering and discontinuation of antidepressant drugs before and during the early phase of pregnancy are worth attempting to prevent the occurrence of this syndrome.” They recommended non-drug therapies such as cognitive-behavioural therapy as the first choice.

Resources are available for both patients and clinicians.

The Therapeutics Initiative at the University of British Columbia has published plain-language recommendations for safely stopping antidepressants, offering step-by-step advice for those considering withdrawal.

For doctors, the Maudsley Deprescribing Guidelines by Taylor and Horowitz provide structured clinical protocols, including hyperbolic tapering schedules and strategies for managing withdrawal symptoms.

Is the Autism Risk Real?

Several experts said the potential for SSRIs to influence neurodevelopment is being brushed aside too quickly.

Dr Jay Gingrich, a professor of psychiatry at Columbia University, pointed to animal studies showing serotonin’s vital role in brain development, particularly in forming cortical maps.

SSRIs, he warned, may disrupt that process. While he cautioned that translating animal data to humans is difficult, he added, “These effects are relatively subtle, but they are there.”

In 2018, Gingrich and colleagues found that SSRI-exposed infants had enlarged gray matter in the amygdala and insula, and stronger white matter connections, compared with babies whose mothers had untreated depression or no depression.

Psychiatrist Dr David Healy reminded the panel that this concern is hardly new. In 2009, a jury found that Paxil caused birth defects and GlaxoSmithKline paid over $1 billion to settle 800 related lawsuits.

“Since that verdict,” said Healy, “five times more women have taken SSRIs during pregnancy.”

Data linking SSRIs to autism, he added, “has existed for more than a decade.”

Despite this, media outlets continue to insist the autism link has been debunked. But as psychiatrist Dr Joanna Moncrieff put it, “Most studies are underpowered…They can’t rule out harm.”

Hence, to say the matter is settled is simply false.

Do SSRIs Even Work?

Moncrieff also challenged the very foundation of SSRI use.

“They change the normal workings of the brain and alter people’s normal mental and physical function,” she said, adding that the benefit over placebo is “absolutely minuscule.”

She acknowledged that depression in pregnancy should be treated, but argued the first question must be: do antidepressants actually help?

“Of course, depression affects a mother’s ability to raise her baby…but that’s exactly why it’s so important to know whether SSRIs will even improve this situation. At the moment, there’s no evidence that they do,” she said.

Instead, she warned, SSRIs “can be difficult to discontinue, impair sexual function, and cause long-term dependence.”

Dr Healy added that SSRIs do not help people who are “severely depressed.” All of the studies are done in primary care settings in people with mild to moderate depression.

“There’s not a single trial of an SSRI that I know of, which was done in hospital settings. They don’t help melancholic patients,” Healy stated.

When Emotions Are Pathologised

Clinical psychologist Dr Roger McFillin cautioned against treating all emotional distress during pregnancy as a ‘disease.’

“When we talk about depression as if it’s this illness, this discreet condition that we can identify, we are misleading people,” he said, warning that society has been teaching people to mistrust their own feelings.

“You learn not to trust your emotions. You judge them as a symptom. You develop fear around them, which is exactly what we have been doing in the United States for the past 35 years,” McFillin said.

He argued that women’s emotions should not be pathologised, but valued. “Those are gifts,” he said. “They’re not symptoms of a disease.”

However, he faced fierce media backlash, which portrayed his comments as misogynistic and patronising—a distortion McFillin described as a deliberate attempt to discredit him.

In truth, it was a call to rethink how society interprets emotional experience.

McFillin’s warning echoes concerns raised for decades by leading critics of psychiatry.

Allen Frances, former chair of the DSM-IV task force, warned in his book Saving Normal, that psychiatry is increasingly medicalising everyday emotional distress, too often treating it with medication rather than recognising it as a normal part of life.

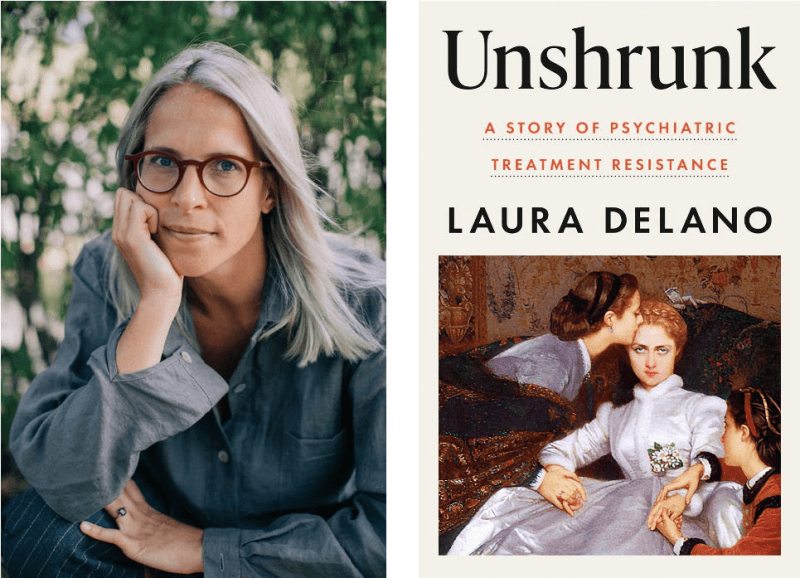

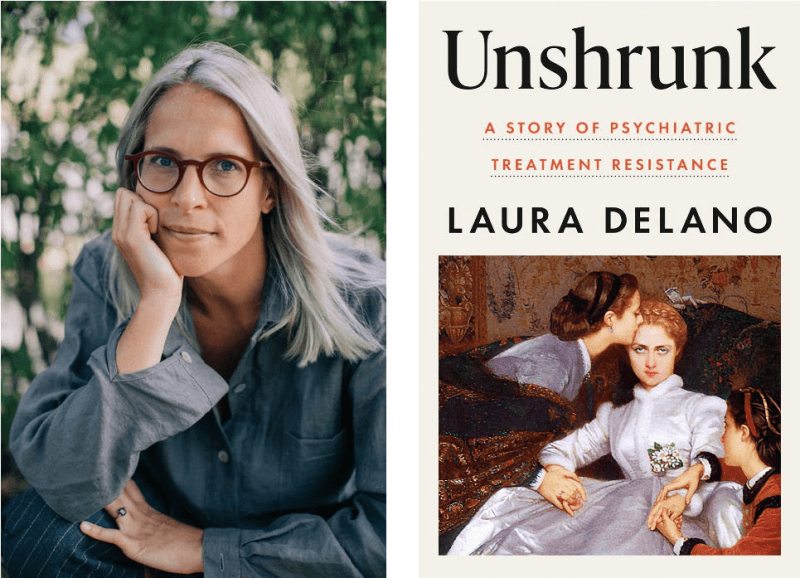

This critique has also been taken up by those with lived experience.

In her memoir Unshrunk, Laura Delano describes how, after years on psychiatric drugs, she learned to embrace emotions she had once been taught to fear, writing that she now allows herself to “just sit and feel.”

Her account reinforces the broader concern that emotions, however painful, are part of the human condition.

In Defence of SSRIs in Pregnancy

Not all panellists were critical. Dr Kay Roussos-Ross, a reproductive psychiatrist, defended SSRIs and, unsurprisingly, was praised by mainstream outlets.

She described the drugs as “life-changing and life-saving” for some women, and said the evidence base—though almost entirely observational—was “robust.”

She argued that SSRIs “need to be in the toolbox” and warned that untreated depression also carries risks.

But she drew controversy when she claimed that “mental health disorders are no different than medical disorders” such as diabetes or asthma.

Witt-Doerring pushed back immediately.

“Respectfully, I would disagree,” he said. “Mental health conditions are very different from physical problems. Physical problems have some basis in pathology—you can point to an area where you’ll correct it, lack of insulin or something like that.”

Depression, he stressed, has no such pathology—despite decades of the false narrative that it was caused by a chemical imbalance.

Urato summarised by returning to first principles.

“We want to see improved outcomes,” he said. “But it is not actually what the data shows—it is marketing from the pharmaceutical industry.’

“The data suggest that women on SSRIs during pregnancy are exposed to chemicals causing complications,” he added.

Transparency Isn’t “misinformation”

The backlash was swift.

Mother Jones called the event a “misinformation fest.” Slate claimed it spread “lies.” The New York Times described it as “alarming” and suggested it “may scare women who need help.”

Media outlets fixated on politics—specifically the association with Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.—and ignored the evidence on display.

This was no fringe gathering but a room full of credentialed experts raising good-faith questions and calling for better informed consent.

It wasn’t anti-psychiatry or anti-woman, despite the media criticism. It was about giving women the truth about what’s at stake for them and their baby.

Republished from the author’s Substack

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.