So, word has it that Twitter has withdrawn from the EU’s Code of Practice on Disinformation, a fact that appears only to be known thanks to a couple of pissy tweets from EU officials. I cannot help but wonder if this is not finally Elon Musk’s response to the question I asked in my article here several weeks ago: namely, how can a self-styled “free-speech absolutist” be part of a “Permanent Task-Force on Disinformation” that is precisely a creation of the EU’s Code?

But does it matter? The answer is no. The withdrawal of Twitter’s signature from the Code is a highly theatrical, but essentially empty gesture, which will undoubtedly serve to shore up Musk’s free speech bad-boy bona fides, but has virtually no practical consequences.

This is because: (1) as I have discussed in various articles (for instance, here and here), the effect of the EU’s Digital Services Act (DSA) is to render the hitherto ostensibly voluntary commitments undertaken in the Code obligatory for all so-called Very Large Online Platforms (VLOPs) and (2) as discussed here, the European Commission just designated a whole series of entities as VLOPs that were never signatories of the Code.

Twitter is thus in no different a position than Amazon, Apple and Wikipedia, none of which were ever signatories of the Code, but all of which will be expected by the EU to comply with its censorship requirements on the pain of ruinous fines.

As EU officials like to put it, the DSA transformed the “code of practice” into a code of conduct: i.e. you had better do it or else.

Compliance is thus not a matter of a signature. The proof of the pudding is in the eating. And the fact of the matter is that Musk and Twitter are complying with the EU’s censorship requirements. Much of the programming that has gone into the Twitter algorithm is obviously designed for this very purpose.

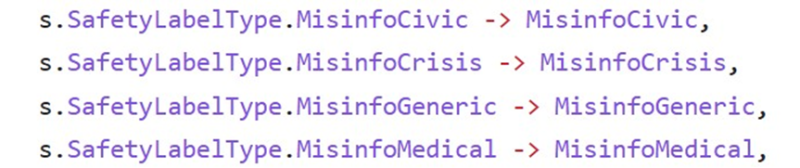

What, for instance, are the below lines of code?

They are “safety labels” that have been included in the algorithm to restrict the visibility of alleged “misinformation.” Furthermore – leaving aside the handy “generic misinfo” catch-all – the general categories of “misinformation” used exactly mirror the main areas of concern targeted by the EU in its efforts to “regulate” online speech: “medical misinfo” in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, “civic misinfo” in the context of issues of electoral integrity, and “crisis misinfo” in the context of the war in Ukraine.

Indeed, as Elon Musk and his lawyers certainly know, the final version of the DSA includes a “crisis response mechanism,” (Art. 36) which is clearly modeled on the European Commission’s initially ad hoc response to the Ukraine crisis and which requires platforms to take special measures to mitigate crisis-related “misinformation.”

In its January submission to the EU (see reports archive here), in the section devoted precisely to its efforts to combat Ukraine-war-related “misinformation,” Twitter writes (pp. 70-71):

“We … use a combination of technology and human review to proactively identify misleading information. More than 65% of violative content is surfaced by our automated systems, and the majority of remaining content we enforce on is surfaced through regular monitoring by our internal teams and our work with trusted partners.”

How is this not compliance? Or at least a very vigorous effort to achieve it? And the methodology outlined is presumably used to “enforce on” other types of “mis-“ or “disinformation” as well.

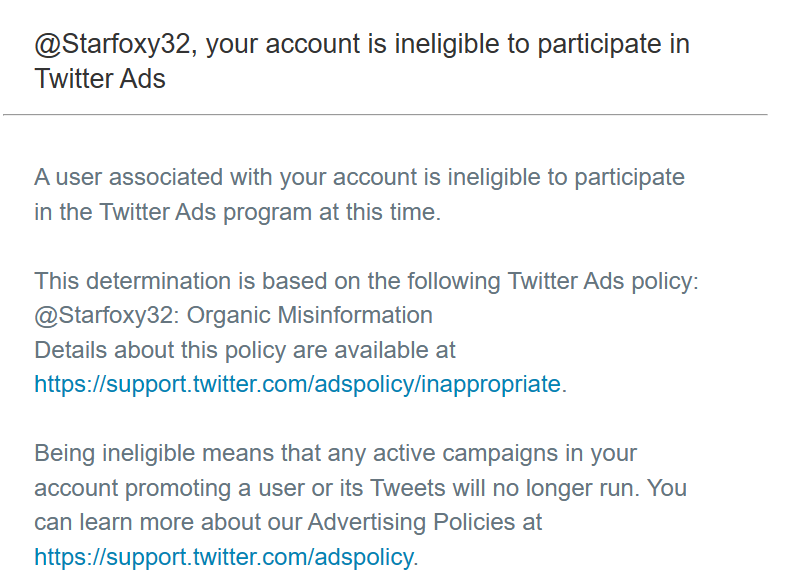

Finally, what is the below notice, which many Twitter users recently received informing them that they are not eligible to participate in Twitter Ads because their account as such has been labeled “organic misinformation?”

Why in the world would Twitter turn away advertising business? The answer is simple and straightforward: because none other than the EU’s Code of Practice on Disinformation requires it to do so in connection with the so-called “demonetization of disinformation.”

Thus, section II(d-f) of the Code reads:

(d) The Signatories recognise the need to combat the dissemination of harmful Disinformation via advertising messages and services.

(e) Relevant Signatories recognise the need to take granular and tailored action to address Disinformation risks linked to the distribution of online advertising. Actions will be applicable to all online advertising.

(f) Relevant Signatories recognise the importance of implementing policies and processes not to accept remuneration from Disinformation actors, or otherwise promote such accounts and websites.

So, in short, vis-à-vis the EU and its Code, Twitter is complying, not defying. Removing Twitter’s signature from the Code when its signature is no longer required on the Code anyway is not defiance. Among other things, not labeling content and/or users as “misinformation,” not restricting the visibility of content and/or users so labeled, and accepting advertising from whomever has the money to pay would be defiance.

But the EU’s response to such defiance would undoubtedly be something more than tweets. It would be the mobilization of the entire punitive arsenal contained in the DSA and, in particular, the threat or application of the DSA fines of 6 percent of the company’s global turnover. It is not enough to (symbolically) withdraw from the Code of Practice to defy the EU. Defying the EU would require Twitter to withdraw from the EU altogether.

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.