How do you get people to make good decisions? You can be negative and punish bad decisions or you can be positive and incentivize good decisions. Our language is full of cliches articulating these options: carrots and sticks, honey and vinegar.

Farmers make decisions every day about what to grow, how much of it to grow, and how to grow it. Whether it’s corn or cows, we look at the various incentives and punishments to decide how to proceed.

Decisions are a complicated and nuanced response to stimuli, both internal and external. Some of us really like cows. Others of us really like corn. These soul-level likes and dislikes are not subject to business or market influence. Often childhood familiarity determines whether we go with animals or plants. We tend to like knowns in our life.

Meanwhile, the food and fiber market has the same influence. One person likes beef, another tomatoes, and another milk. We might read something that makes us question a certain product. Or we may read something that makes us put it on our plate for the first time.

The market constantly ebbs and flows as information, friends, social media influencers, and personal health feelings impact purchasing decisions. The faster decisional consequences can be linked to the choices we make, the better our response. This is one reason why we have a statute of limitations for many crimes.

Decisional consequences are one of the most moral and authentic elements in both personal and societal development. When people don’t suffer the consequences of poor decisions, they tend to continue down a wayward path. On the other hand, when people don’t receive incentives for doing good, it thwarts development toward positive progress.

Failing to bear the costs and consequences of bad decisions is as perverse as failing to incentivize the costs and consequences of good decisions. This seems elementary enough to not even mention, but we often create public policy that seems to deny this fundamental axiom.

A case in point is federal government safety nets. Often begun with every good intention, they frequently break down after years of implementation. Government programs tend to grow more bureaucratic, becoming more interested in expanding power and budgets than in solving the problem they were chartered to solve.

When President Franklin D. Roosevelt froze wages, businesses sought new incentives for employees and opted for health insurance. Once health care market decisions left the individual level, the short chain between choice and consequence elongated. Eventually, this morphed into the Affordable Care Act that is now widely regarded as creating more problems than it started.

The local one-room, community-funded, and controlled school house gave way to state programs and eventually a federal program. “No Child Left Behind” now leaves some 46 percent of children left behind in reading based on current standardized tests. The safety net of public education is now widely regarded as inferior to private, charter, and homeschooling.

A retirement safety net called Social Security began as a 1 percent employee payroll tax. Today it’s far higher and any financial adviser knows that if that money had been invested in the stock market, it would have grown far more than in government coffers. Investment decisions that used to be made individually became neglected as millions of people came to believe the government would take care of them in their old age.

Most of us can list numerous programs and their influence on individual decisions, generally negatively. If someone else will always pick me up when I fall down, I’m not nearly as careful where I step. That’s sociologically axiomatic.

This brings me to soybean farmers. US crop insurance programs, renamed from subsidies for political acceptance, started during the Depression as a safety net for farmers. Handpicking just six commodities for special incentives (corn, soybeans, wheat, cotton, rice, and sugarcane) this nearly century-old program dominates American agriculture. Further, it influences farmer decisions down to the field level: “What am I going to grow here?”

Farmers have many choices as to what to grow. Although farmers are known for their product (dairy farmer, orchardist, vegetable grower, livestock) they are really caretakers of a spot of creation. As a farmer, the deed recorded at the county clerk’s office says I own this land, but in reality I’m a sojourner on something I did not create. The soil, water, and sunlight hitting my fields are ultimately not possessions as much as resources I have the privilege to steward.

The point is that the land that grows soybeans could grow a host of other things. The farmer must look at that array of options and choose something. Any land that will grow soybeans is inherently good land; nobody grows row crops on rock piles. The better the land, the more diversified the options.

Why should the American taxpayer guarantee the viability of soybean farming when the world has too many soybeans? Markets—and farmers—are supposed to respond to supply and demand. While their predicament of losing $90 per acre this year due to China’s retaliation for President Donald Trump’s tariffs (China bought 23 percent of the US soybean crop in 2024) is heartbreaking, this dependency on a multi-decade government safety net has created this dilemma.

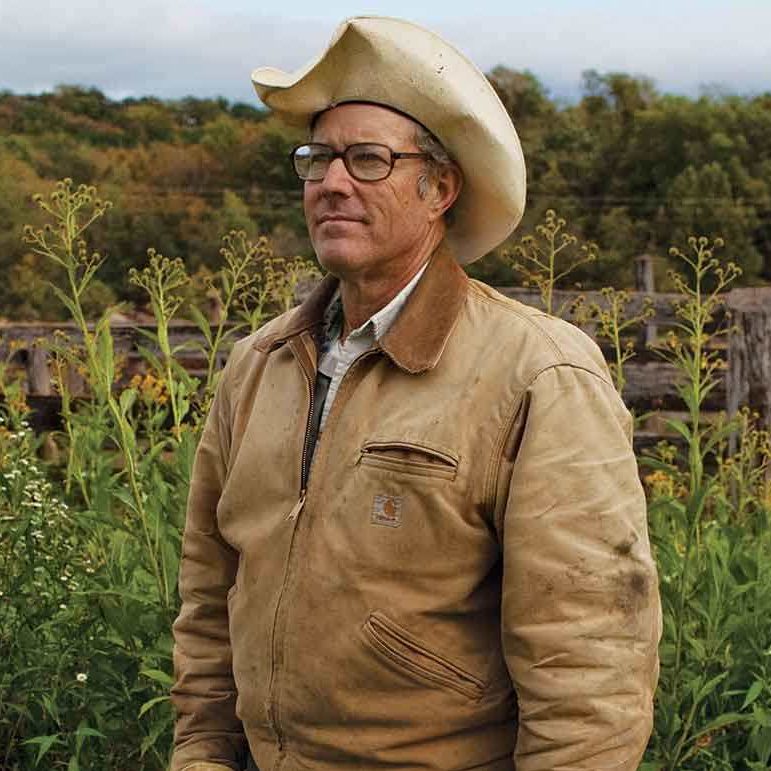

I encourage all farmers to wean themselves from the government safety net. I’m a full-time farmer and I don’t take a dime of government money. My decisions create consequences due to my choices. By not using chemical fertilizers, when Vladimir Putin invaded Ukraine and fertilizer prices skyrocketed, it had no impact on our farm because we use compost instead of chemicals.

All farmers have a choice, and the faster our society respects them enough to put their choice consequences in their hands, the sooner farmers will make more creative and innovative decisions. The crop insurance safety net prejudices decisions and incentivizes dependence on one crop and one agency. Sooner or later, making the same choice every year because it’s easy due to a safety net will show its weakness, because safety nets eventually shatter, especially if they depend on politics.

I challenge forward-thinking soybean farmers to think about growing something else. Cattle come to mind. We’re desperately short of cattle, and the price is soaring to historical highs. Converting row crop ground to legacy perennial prairie polycultures under well-managed cows could be a ticket to stable profits and a happier life. That might be a decision with wonderful consequences.

Republished from Epoch Times

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.