We live in what is probably the most nihilistic era in the history of humankind. Most English-speaking people have probably heard the term, ‘nihilism,’ but I’m willing to bet that not many know its precise meaning. The term comes from the Latin for ‘nothing,’ to wit, ‘nihil,’ so that nihilism would literally mean ‘a belief in nothing.’

Some people may recall the film, The Neverending Story, which narrates the attempt, by several characters, to stem the expansion of ‘the nothing,’ which devours everything in its way. It can be read as an allegory of the cyclical efflorescence of nihilism, which has to be combated all over every time. The film also offers a way to resist this growth of ‘the nothing,’ which has to do with imagination and courage, and is worthwhile reflecting on. Consider this: if we were not able to imagine an alternative to a certain state of affairs – such as the fraught present – and the courage to change it, things would stay as they are, or get worse.

An internet search will yield several ‘definitions’ of nihilism, such as this one: ‘a viewpoint that traditional values and beliefs are unfounded and that existence is senseless and useless.’ For present purposes the following one is more apposite:

…a doctrine or belief that conditions in the social organization are so bad as to make destruction desirable for its own sake independent of any constructive program or possibility.

Narrowing the circle of the meaning of nihilism, this discussion of the concept includes the highly relevant statement:

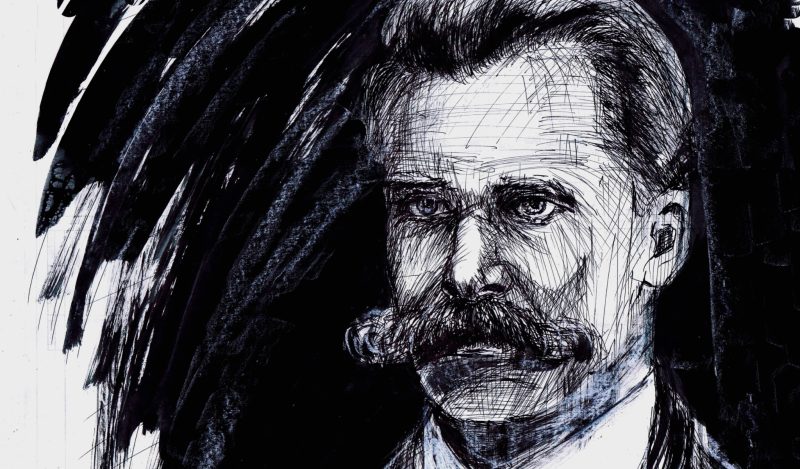

While few philosophers would claim to be nihilists, nihilism is most often associated with Friedrich Nietzsche who argued that its corrosive effects would eventually destroy all moral, religious, and metaphysical convictions and precipitate the greatest crisis in human history.

To anyone who is aware of what has been unfolding over the last four-and-a-half years, the two ‘definitions’ of nihilism, immediately above, would probably seem eerily pertinent to this process as well as to one’s own response to it. Talking about ‘destruction (evidently being) desirable for its own sake’ on the part of some, or about the ‘corrosive effects’ of nihilism that would, with time, annihilate religious and moral beliefs, is so close to one’s current experience of the world as to cause distinct discomfort, if not anxiety. So, where did the current axiological (value-related) fog of nihilism come from? Did it predate the Covid era?

It has come a long way indeed, as I shall presently show. Some readers will recall my essay on the waning of authority (as analysed by Ad Verbrugge in his book on the subject), which gives an historical perspective on the events and cultural changes that entrenched a nihilistic sensibility. Or you may be reminded of the article on wokism, where I discussed a cultural phenomenon of fairly recent provenance – one which was probably launched by those who would benefit hugely from weakening the sense of identity that women and men worldwide shared for millennia, and which has been the object of a relentless attack by various globalist agencies, from education to medicine and the pharmaceutical industry to the business world.

Anyone who would question the above statement regarding men and women should consider that it is not designed to deny the fact that historical evidence suggests homosexuality to have been around since the earliest human societies, albeit with a difference. Take ancient Greece and Rome, for example. In the former, the love between men was valorised, and the ancient lesbian Greek poet, Sappho, was responsible for the name of the island on which she lived, Lesvos (or Lesbos) being applied to homosexual women.

The point is that, although such men and women were homosexual, they never denied their masculinity or femininity. But the woke movement has gone out of its way to insert the virus of identity-doubt into the field of gender, in this way causing a plethora of pain and confusion in families worldwide, and exacerbating an already entrenched collective state of nihilism.

So, how far into the past do the roots of nihilism – the belief that nothing has intrinsic value – stretch? As far back as the ancient world, in fact. In his first notable philosophical work, The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music (1872), Friedrich Nietzsche (as a young professor of philology) constructed an account of the distinctiveness of ancient Greek culture that was wholly novel, compared to the accepted views of his time. (See also here.)

In a nutshell, Nietzsche argued that what differentiated between the ancient Greeks and other contemporary societies was their genius for combining an appreciation for (what was to become scientific) knowledge with one for the indispensable role of myth (whether in the guise of a panoply of myths, such as those the Greeks evoked to understand the world, or in the form of religion, which always has a mythical basis). Put differently, they found a way to endure the unsettling thought that everyone has to die sometime, by combining a creative affirmation of reason with an acceptance of the inescapable role of unreason, or the irrational.

More specifically, Nietzsche understood Greek culture as revolving around the tension field established by what their gods, Apollo, on the one hand, and Dionysus, on the other, represented, and he demonstrated how the tension between them was what gave ancient Greek culture its uniqueness, which no other culture displayed. Apollo was the ‘shining one,’ the sun god of visual art, poetry, reason, individuation, equilibrium, and knowledge, while Dionysus was the god of wine and ecstatic loss of individuality, and also of music and dance, excess, irrationality, drunken revelry, and the abandonment of reason. It is noteworthy that music and dance differ fundamentally from the other arts – as Plato knew when he stated that, in his ideal republic, only military-type music would be allowed, instead of the wild, corybantic music played at Dionysian and Cybelian festivals.

In passing, it should be noted that corybantic music – from ‘Corybantes,’ the attendants of the goddess Cybele, whose creative mythic function was related to that of Dionysus – among the ancient Greeks, which does not appear to have an equivalent in modern music (except perhaps for certain varieties of heavy metal) was recognisable by its frenzied, intense, wildly unrestrained character, and concomitant dance movements during rituals at religious festivals.

Moreover, according to Nietzsche, Greek culture showed that, for a culture to be vibrant, neither of these two primordial forces could be abandoned, because each catered for a distinctive human faculty – on the one hand Apollonian reason (as enshrined in ancient Greek philosophy and the beginnings of science, particularly in the work of Aristotle), and on the other Dionysian unreason, embodied in Dionysian festivals, where revellers behaved in a rowdy and anything but civilised manner – somewhat akin to what high school or college students sometimes do during ‘raves’ or freshman initiation rituals.

I do not have the space here to provide an exhaustive discussion of this complex text; suffice to say that Nietzsche’s incisive interpretation of Greek tragedy reveals its emblematic character as far as the countervailing values attached to these two Greek deities, respectively, are concerned. The dramatic action, represented by clearly individualised actors (most importantly the tragic heroine or hero), whose unfurling fate is presented as being subject to cosmic forces that they cannot control, is Apollonian, while the intermittent, sung commentary by the chorus, consisting of actors dressed as satyrs (half-human and half-goat), is Dionysian. Interestingly, the term ‘tragedy’ derives from the Greek for ‘goatsong.’

As Nietzsche points out, the ambivalent biological status of the chorus is significant – half-goat, half-human – insofar as it highlights the inescapable animal side of our nature, which Freud (Nietzsche’s psychoanalytic counterpart) also stresses by exposing the unconscious, irrational sources of motivation of human actions. The satyr as mythical being represents virility, and ipso facto sexuality, which is admittedly always refracted through the lens of culture (no ‘pure’ sexuality is to be found in any human being). Greek tragedy therefore foregrounds the co-presence of the Dionysian (irrational) and the Apollonian (rational) forces in human culture, which is unsurprising: each one of us is a combination – an uneasy one, to boot – of Dionysian and Apollonian forces, and unless a culture finds ways to do justice to both, such a culture will wither and die, according to Nietzsche.

In fact, as the German thinker demonstrates in The Birth of Tragedy, this is what has been happening in Western culture since the time of the Greeks; hence the growth of nihilism. To be more precise: instead of preserving the life-giving tension between the Apollonian and the Dionysian, Western culture has gradually repressed the latter, if not elided it altogether, allowing the Apollonian to triumph in the guise of science, or rather, scientism – the belief that every aspect of culture and society should be subjected to a scientific makeover, from art, religion, education, and trade to architecture and agriculture. Nietzsche’s claim is not that science is bad per se, but that, unless it is counterbalanced by a cultural practice that allows human irrationality an outlet, as it were (in certain forms of dance, for example), it would be detrimental for human culture and society.

Insofar as all religions have a mythical basis (usually in narrative form), the dominant Western religions are no exception; the story of Jesus as the Son of God being the foundational one in the case of Christianity, for example. But in the course of what may be called the ‘rationalisation of Christianity’ (that is, the increasing role that Biblical science and criticism started playing in it since the 19th century), the acceptance that Christian faith is less based on scientific demonstrability than on faith in the divinity of Christ, has waned considerably.

The result has been the gradual disappearance of the Dionysian element in Western culture, which paved the way for nihilism to assert itself. After all, with the advent of the historical Western Enlightenment, which proclaimed the triumph of reason over ‘superstition,’ the salutary role of religion, with its mythical, irrational (Dionysian) foundation, has been undervalued, even if there are still many people who practice it.

Some may question the claim that a religion such as Christianity has a Dionysian foundation. Recall that Dionysus represented the ‘loss of individuality,’ as in the Dionysian revels where participants felt as if they were merging with one another. Compare the celebration of Mass in the Christian Church, where the drinking of wine and eating of bread, as symbols of the blood and body of Christ, signify a becoming one with the latter as the Saviour and ‘Son of God.’

In the Catholic Church’s interpretation of Holy Communion, the belief in ‘transubstantiation’ prevails; that is, that the bread and wine substantially change into the body and blood of Christ. Moreover, the ‘community of the faithful’ also represents the subsumption of the individual in the group of believers. And none of this is based on scientific knowledge, but on faith, which is hardly rational, as the medieval philosopher, Tertullian, intimates when he proclaims: ‘Credo, quia absurdum’ (‘I believe, because it is absurd’) – an Enlightenment interpretation of his original remark.

But why did the incremental scientisation of culture mark the emergence of nihilism? Doesn’t science retain an admission of the intrinsic value of things? No, it does not – as Martin Heidegger has demonstrated in his profound essay, The Age of the World Picture (the relevance of which is discussed in my paper on ‘worldviews’), modern science reduced the world of experience, which had always been (and still is, in one’s everyday pre-scientific approach to it) shot through with value, to a series of measurable and calculable objects in space and time, which paved the way for technological control. This amounts to the clearing of the deck, so that nihilism can take root. To be sure, ordinarily, or pre-scientifically, nature, one’s favourite tree in the garden, your pet cat or dog, and so on, are all experienced as being valuable. But when these things are subjected to scientific analysis, their axiological status changes.

Capitalism, too, has played its role in this process, in the sense that, when value is reduced to exchange value, where everything (every object) is ‘valued’ in terms of money as the common denominator, things lose their intrinsic value (see my paper on architecture as consumer space in this regard). Can one put a price on a beloved pet, or even a cherished piece of clothing, or jewelry? Sure one can, you would say. But I’m willing to bet that, after years of wearing your cherished diamond ring, or your preferred evening dress, it has accrued what in Arabic is called baraka, or blessed spirit – no new item of its kind could really take its place.

The link between capitalism and nihilism is too encompassing a theme to address adequately here (see my book on nihilism, which appeared electronically in 2020, and is slated to appear in hard copy this year). One could say, succinctly, that while capitalism – in the 19th century and for part of the 20th century, for instance – concentrated on producing products, with an emphasis on quality, durability, and functional value, its nihilistic effects were not paramount.

One can endow a well-made pair of shoes, or suit, or set of crockery and cutlery, let alone a beautiful work of art, with value beyond its exchange (monetary) value. But when the focus on product quality was relinquished in favour of financialisation (where money itself, instead of tangible products, became a commodity), its nihilistic character became conspicuous. How so?

Eight years ago Rana Foroohar, an economic and financial journalist, published a book titled Makers and Takers (Crown Business Publishers, New York, 2016) that goes some way towards clarifying the link between capitalism and nihilism, although she does not thematise the latter. In the book she claims, startlingly, that market capitalism in the US is ‘broken’ and in a synoptic article in TIME magazine (American Capitalism’s Great Crisis, TIME Magazine, May 23, 2016, pp. 2228) she sets out her reasons for this claim. Having enumerated the various ‘prescriptions’ for resolving the economic crisis, advanced by the candidates in the 2016 US presidential election, Foroohar writes:

All of them are missing the point. America’s economic problems go far beyond rich bankers, too-big-to-fail financial institutions, hedge-fund billionaires, offshore tax avoidance or any particular outrage of the moment. In fact, each of these is symptomatic of a more nefarious condition that threatens, in equal measure, the very well-off and the very poor, the red and the blue. The U.S. system of market capitalism itself is broken…To understand how we got here, you have to understand the relationship between capital markets – meaning the financial system – and businesses.

Foroohar then sets out to explain this relationship. Homing in on what she identifies as the culprit, she concludes that:

America’s economic illness has a name: financialization…It includes everything from the growth in size and scope of finance and financial activity in the economy; to the rise of debt-fueled speculation over productive lending; to the ascendancy of shareholder value as the sole model for corporate governance; to the proliferation of risky, selfish thinking in both the private and public sectors; to the increasing political power of financiers and the CEOs they enrich; to the way in which a ‘markets know best’ ideology remains the status quo. Financialization is a big, unfriendly word with broad, disconcerting implications.

Needless to point out, this was in 2016, and today our concerns about nihilism have less to do with capitalism than with the cynical nihilism evident in the actions orchestrated by the group of multi-billionaires who are hellbent on destroying the lives of the rest of humanity by hook or by crook. These sub-humans evidently hold human lives – in fact, all life-forms – in such low regard, that they did not hesitate to promote bioweapons as legitimate ‘Covid-vaccines,’ while probably knowing full well what the effects of these experimental concoctions would be.

That speaks of a nihilism beyond anything the world has seen, with the possible exception of the Nazi death camps of the 1940s. Nietzsche would turn in his proverbial grave. How does one get beyond such nihilism? That is a topic for a future post, and again, Nietzsche will be the main source of insight into this possibility.

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.