It has been said that original sin is the only empirically verifiable Christian doctrine; it should be obvious that we humans positively have a tendency to do things that we either regret or at least should regret. And yet, the modern world has moved away from using the word “sin” at all.

Instead we use euphemisms like “inappropriate” to avoid implying the existence of metaphysical good and evil. As we begin the Christian season of Lent, I’d like to suggest a recovery of the word sin as an explanation of what happened to the world as a result of the spread of mass hysteria in 2020. What happened was not merely “inappropriate” or even merely illegal, but rather it was sin, and if we want to move forward as a civilization there must be some mechanism of repentance and reconciliation.

Sin is Not a Scary Religious Word

No doubt one of the reasons the modern world has stopped using the word “sin” is that for centuries now the secular Western world has moved in a decidedly post-Christian direction and calling things sins would be seen to be a statement of religion. Instead, the Hebrew word for sin is not religious at all, it literally means something along the lines of “to miss the mark” as in archery. The Catechism of the Catholic Church gives an initial definition of sin as “an offense against reason, truth, and right conscience” (1849) before proceeding to discuss love of God and God’s law. Sin as a concept precedes religion.

Both Aristotle and Aquinas acknowledge that happiness is the result of virtue (both intellectual and moral) and that moral virtue is a type of habit that disposes the person to do the right thing, in the right way, in the right amount, at the right time, and for the right reasons. It is the moral equivalent of always hitting the bullseye in archery. Any deviation away from that is “missing the mark.” It is an “offense against reason, truth, and right conscience.” It is therefore properly called a sin.

The Predisposition to Miss the Mark

Part of the doctrine of original sin is that both man’s intellect and will are weakened as a result of contracting it. Man now only knows the good with difficulty and, even when he knows it, often has great difficulty accomplishing it; he doesn’t reliably know where the mark is and even when he does he will miss it anyway.

This fact about humanity was established empirically through a variety of psychological experiments:

In the 1950s, Solomon Asch discovered that 75 percent of people fail to reliably describe what their eyes report to them when surrounded by actors giving the same wrong answers, even to the point of seeing a reality that isn’t there.

In the 1960 Stanley Milgram observed that 65 percent of participants would continue administering electric shocks to an innocent person well into the fatal range simply because an authority figure told them to do so.

In 1971 Philip Zimbardo demonstrated the ease with which humans can be convinced to choose cruelty against a purely arbitrary out-group in the Stanford Prison Experiment.

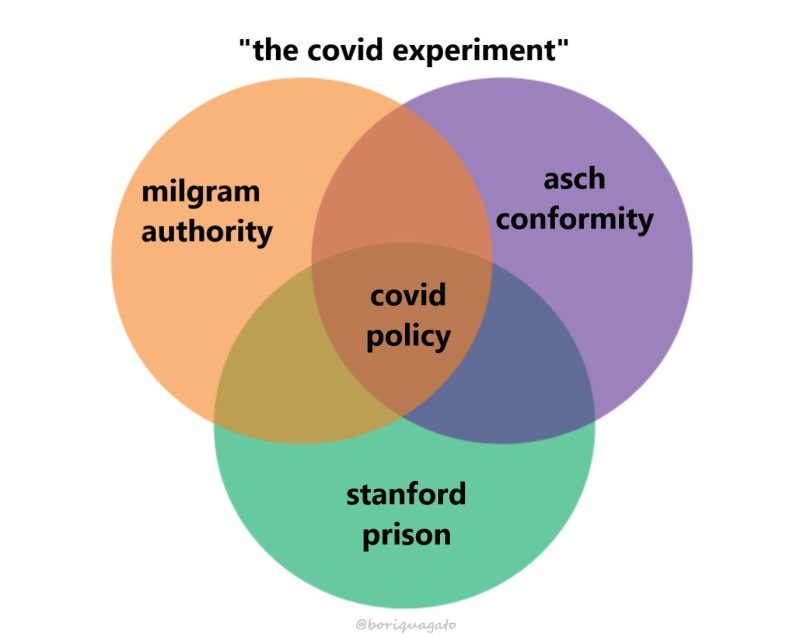

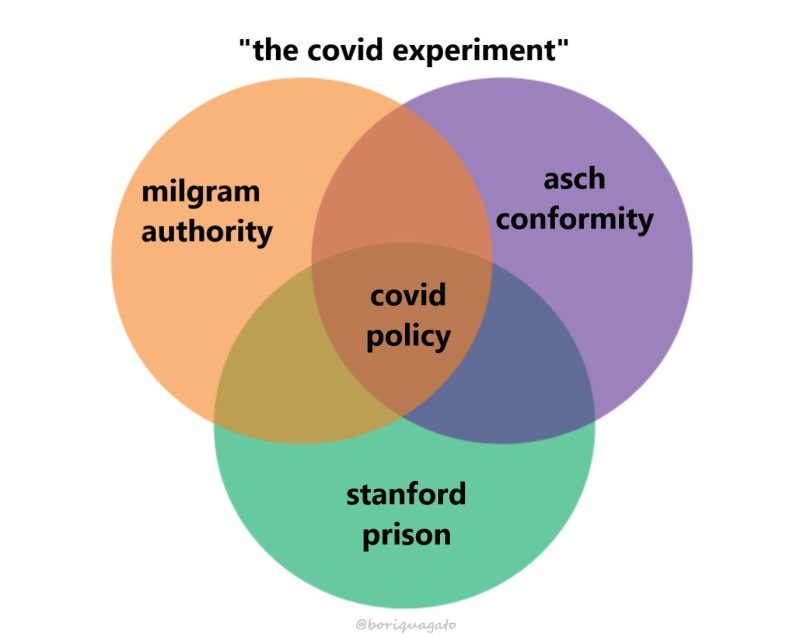

As the brilliant el gato malo observes, all three of these dynamics were on display these past three years:

Furthermore he continues:

most subjects fail ALL these tests.

passing all 3 at once is no mean feat.

everyone likes to claim they’d be the one to stand free, but history shows the lake wobegon lie of such self-regard: most people do not pass tests with 10% pass rates. it’s just a fact. one can own it or one can try to fool oneself and others.

We should be open to considering that the insanity of the past three years was possible precisely because far too many of us believed that it was impossible. Even after two world wars and multiple economic and social crises, the overly optimistic myth that we are so much smarter and more rational than our ancestors has continued on, even as the intellectual and moral virtues have been in steady decline.

In 1942 Fulton Sheen wrote the following in God and War: “Dictators are like boils, superficial manifestations of an inner rottenness. They would never have come to the surface if there had not been the proper conditions in the world from which they came.”

For over two years we flirted with outright dictatorship and we would be foolish to think that the same forces that sought outright control in 2020 are suddenly healed of their moral infirmity. I therefore suggest the following lessons we can and should learn from this horrible experience:

- Our Covid response was fundamentally a moral failure. First and foremost, it would have been impossible for fear to spread so effectively in 2020 if it were not for the widespread vice contrary to perseverance which Thomas Aquinas calls effeminacy. He defines effeminacy as the vice that makes “a man to be ready to forsake a good on account of difficulties which he cannot endure.” Unlike mere decades ago, we were not willing to endure the slightly elevated chance of death from a bad cold and flu season and therefore were willing to forfeit nearly every societal good and indeed embrace utter cruelty against our neighbors. It is obviously cruel to lock people in their homes indefinitely. It is obviously cruel to force another human being to muzzle himself because you don’t want to breathe the same air as them. It is obviously a malicious lie to call any experimental drug “safe and effective.” It is obviously utterly heinous to coerce someone into injecting such a substance. The fact that none of these things even worked is not what makes them wrong, but it certainly elevates the gravity of the evil done. If opinion polls are to be believed, the vast majority of people “missed the mark” and sinned either directly or by serving as accomplices to the wrongs which were committed.

- The majority will always value lesser goods such as social acceptance over the truth. This is a bitter pill to swallow for the children of “The Enlightenment.” We are not disembodied intellects who can be educated into being reliably reasonable. Most of us filter reality not through our senses and intellect but rather through more base instincts and tribal concerns. The psychological experiments mentioned above took place in the context of asking how it is that Nazi Germany could occur, but instead stumbled upon the troubling answer that we should instead marvel that such historical atrocities don’t happen more frequently. Humans reliably “miss the mark” especially in moments of stress or crisis. A well-structured society includes safeguards and checks and balances to prevent outbreaks of madness from leading to self-destruction.

- Those who stand aloof from the madness of the crowds will always be a small minority. Even if one denies the doctrine of original sin, we still have the empirical fact that only a tiny minority of humans will pass any of the experiments mentioned above, let alone all three. In a society which inculcates moral virtue, it is possible to grow this group, but it is important to note that there are natural differences in us that make passing these tests more or less difficult. For example, I am at the 23rd percentile in agreeableness according to one personality inventory. In math classes, I was the one who always pointed out when the answer in the back of the book was wrong. I recognize that I had a much easier time discerning the truth than others.

- Because such a group will always be a minority, it is important for these people to be loud, well networked, and organized. The cowardice of many voices and the censorship of others created the dynamics of the Asch Conformity experiment in real life. So many people effectively hallucinated a dire plague which required an utterly cruel response because the only voices surrounding them were the voices of panic. Even one voice could have shaken some of them out of the spell, just like we all learned as children when reading The Emperor’s New Clothes. This proves the absolute necessity of organizations like Brownstone Institute, as both legacy media and academia utterly failed the test.

- Guilt is good. Repentance is good. Shame for the unrepentant is also good. As I argued in my first article for Brownstone there needs to be a reasserting of the moral order if we have any hope of societal recovery from these dark years. I suggested that punishing some will help lead most to some acknowledgement of guilt. Calls for general amnesty or accusations that those of us who got things right only did so through luck are lame attempts at self-absolution. To apply the logic of the confessional: there can be no reconciliation without contrition and firm purpose of amendment. It is important then to demand the attitude of mea culpa, mea culpa, mea maxima culpa even among the most stubborn. I think here especially of those in charge of organizations who should have known better and yet remained silent and complicit.

Conclusion

Traditionally, the Collect of the first of the three Sundays preceding the beginning of Lent contained the beautiful request “that we who are justly afflicted for our sins, may be mercifully delivered for the glory of Thy name.”

I’d like to suggest that even those reading without a religious background can certainly identify with the angst of knowing the affliction we all experienced and continue to experience as a result of our collective “missing the mark” beginning in 2020.

While I recognize that we all won’t be celebrating Ash Wednesday and Lent together, I do think that the annual practice of admitting fault and resolving to make amends has never been more necessary than this current year of our lives. We got into this mess by collectively hiding in denial from the reality of “Remember, O man, that dust thou art, and to dust thou shalt return.” To begin to heal we need some form of widespread repentance and acceptance of the truth.

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.