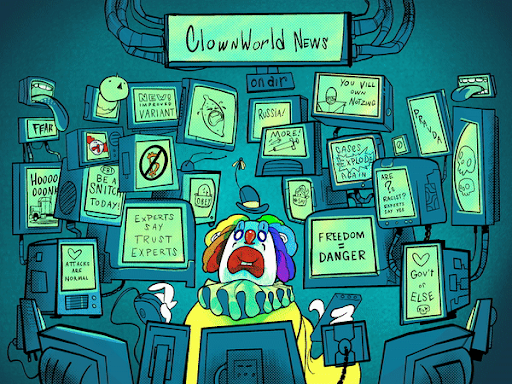

A world weary clown, slightly reminiscent of Max Schreck, stands before a purpling crepuscular sky as he sports a Mickey Mouse vax and crossbones pin on his yellow jumpsuit and balances a pink balloon-animal syringe with an elongated, white-gloved finger. A blue and red stethoscope with a horn for its chest piece floats around his neck. A too-small, pointed yellow hat reading “XPERT” hovers above his balding head of graying red hair.

Once a symbol of cheerful nihilism used to mock the absurdities of an increasingly oneirataxic society that embraces notions that boys can be girls and girls can be boys, this clown has continued, for the past two and a half years, to smile in the face of the untruths that have eroded the foundations of Western civilization.

Earlier this summer, he welcomed people to join him in smiling in the face of these destructive deceits. He invited them to join him for a night of fine art, performance and free speech. From a flier that circulated around the internet in communities that still value such things, he beckoned them to find him in Pueblo, Colorado at “The Truth Show” which kicked off on July 1, 2022.

Pueblo, Rock City

Pueblo has never quite been known for its bustling art scene or as some cultural epicenter. Yet, in many ways this working-class town with deep-seated ties to steel and rail is the perfect place to host an event intended to lambast, lampoon, and impugn a society where public-private partnerships go unquestioned, celebrity businessmen are beyond reproach, and propaganda is a synonym for Truth.

Roughly an hour south sits Ludlow, which, just over a century ago, served as the flashpoint in the Coal Mine Wars when the state was dominated by a handful of politically connected corporations that most notably included the Rockefeller-owned Colorado Fuel and Iron Company (CF&I).

Many of the miners employed by companies such as CF&I felt they were being unfairly compensated for their labor by a system rigged against them; they felt their working conditions were exceedingly dangerous. Hence, in September 1913 they went on strike seeking to have these complaints redressed, as well as gain recognition for their union.

As a consequence, they were kicked out from the company towns in which they lived and upon which they were dependent. Many relocated to strategically placed tent colonies intended to hinder the movement of strikebreakers. The mine operators in turn retained the services of the Baldwin Felts Detective Agency to engage in a harassment campaign against the miners intended to provoke a sufficiently violent response from the workers to warrant the governor of Colorado to deploy the National Guard, a goal they accomplished by October.

In achieving this, at least some of the financial burden of maintaining order and protecting the mines shifted from the corporations to the state government. It also allowed for the unofficial declaration of martial law and suspension of constitutional rights as the militias routinely jailed and harassed workers and their families.

On the morning of April 20, 1914 violence finally broke out between the workers and state militia at Ludlow, the home of the largest of the tent colonies. Historians remain uncertain about which side initiated the day’s hostilities, but by evening the colony was ablaze and roughly 25 were dead – many of whom were children. Fighting broke out at other encampments when they received word of what happened at Ludlow. Eventually, the governor of Colorado had to request federal assistance. The violence ended after 10 days, although the strike carried on for another seven months, after which there were mass arrests, mostly of workers.

In the wake of these events in Ludlow, one of the greatest casualties was the reputation of John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Fortunately for Rockefeller, he was able to find the money to hire a good PR team.

“It was almost going to be pitchforks and lanterns, you know. [They] were going after the Rockefellers and were taking these guys down, so [the Rockefellers] needed to change the way that people thought about them so they did this thing called philanthropy. Right? So, basically buying off people’s opinions. But [this] really didn’t change the way they treated people.”

This is how Jeff Madeen, the host of The Truth Show, concluded his retelling of the story in a phone interview. Completely unsurprised by how few people today are familiar with this dark tale of the American West involving one of the nation’s most revered titans of industry, Madeen said, “When I was a kid I think we got probably more real Truth and real history and it’s been dumbed-down over time and it’s especially bad now.”

“I think Common Core and that kind of crap, you know, doesn’t teach critical thinking so, you know, kids don’t have a way to really think about things,” he added.

Originally from Elgin, Illinois, Madeen attended art school in Chicago where he lived for about 10 or 11 years. In what he described as his heyday of 1977-1983, Madeen would hang out at now-shuttered erstwhile Chicago subculture institutions like Exit, Neo, and Club 950. He knew Al Jourgensen and some of the people from Wax Trax! For a period he had a place on Lincoln across from the Golden Apple.

That was when “there was good shit happening,” Madeen said.

However, as time marched on, Madeen explained, a lot of people moved to New York. Chicago never quite got the recognition it deserved for the music scene it had back then. And “things sputtered out.”

Plus, he said, eventually he had a kid, which made him less of a rocker.

Since his heyday, Madeen spent time in the nearby Chicago suburb of Evanston before moving to Durango in 1995. Around 2007, Madeen said, he became more acutely aware that our society was approaching some kind of crisis for which most people were and still are ill-prepared.

“It has to do with the money system and the amount of debt that countries have, as well as banks have, [and] individuals have,” he elaborated. “I don’t have any debt and I hadn’t for quite a while,” he added proudly. “Kind of the way I played it. But there are others, you know. God knows!” he exclaimed before accentuating his point, “I don’t get to Denver that often, but there are, I mean just thousands of homeless people up there.”

According to Madeen, what we’ve seen so far over the past 15 years has only been the start – things aren’t going to get better.

Another major part of the problem in our society, Madeen added, is what he refers to as a “slab culture” in which “there’s so many people staring at devices all day long, not really experiencing the real world.”

“That’s sad,” he sighed, “[But] that’s how people are controlled – not able to think about the world.”

Art, Madeen believes, can be a means to wake people up to what is going on around them.

In 2016 Madeen moved to Pueblo where, a year later, he opened the Blo Back Gallery, starting with what he described as a long narrow gallery which he affectionately refers to as the “O.G. Gallery.” Blo Back hosted its first show that December and continued to regularly host shows thereafter. At the time, the building also housed an automotive repair shop, the owner of which rented the space from Madeen. The building also contained Madeen’s home up on the second floor.

About two and a half years after Blo Back’s doors opened, now the final days of the Before Times, Madeen said his tenant decided to move out. Not wanting to live above another place that serviced cars, he chose to expand his gallery and put in a stage. “[Now] we have musicians that are touring through kind of on a regular basis and [we] also rent it…” Madeen said in mid-July. “The Rocky Mountain Metal Smiths are in town [for] a convention…They’re going to come here about 5:30 and they’re going to play games and drink and have a good time. And then tomorrow it’s the 20-year class reunion for Pueblo West High School. Monday [there’s] a touring band that’s going to play here.”

But every month there is still a show and in July that show was The Truth Show. Born out of conversations with friends and colleagues that travel in circles that still value free speech, liberty, and art, Madeen decided Truth would be a good theme for a show.

A Small Circle of Socially Distanced Friends

Washington state was the first state in the US with a confirmed Covid case in January of 2020. It was also the first state with a death officially attributed to Covid. Residing in Dayton, Washington, Jordan Henderson though didn’t think much about Covid – at least not at first.

“I didn’t pay a tremendous amount of attention to it because I was used to seeing these sorts of things, like, you know, bird flu and swine flu and Zika. It just seemed like the usual scare-story, which, in a way, it was. But once the lockdowns started happening, I started paying more attention because it was going further than anything had before. And then we got notice here in Washington state that Washington state was going to lock down.”

Henderson was immediately skeptical of both the threat and the response. In Washington state, he said, “They didn’t have enough tests [to diagnose Covid]. Right? So they told the doctors, they said, ‘Only test people who you think have Covid.’ And that’s what the doctors did in Washington state. And most of them came back negative, meaning that the symptoms were the same [as other illnesses]. The doctors couldn’t detect a new disease based upon symptoms. Right? So that was like a huge red flag. But anyways, they said the lockdown was going to come.”

People weren’t going to stand for this though, Henderson thought. They’d surely be irate. So Henderson tried to take action. “I remember sitting down with my sister and [we] started calling people we knew, friends and acquaintances, being like ‘Hey what are we going to do about this? Let’s put together a protest. Let’s do something!’ This is before the lockdown actually began, after we got notice of it. And no one was interested. A shocking number of co-workers, acquaintances, they were okay with what was happening. They didn’t seem to see any issue with it.”

Somewhat disheartened, Henderson didn’t know what to do. He had just committed to art as a full-time business. He had a lot on his plate. He didn’t didn’t have the time to take on the lockdowns alone.

Then maybe a month later, Henderson explained, just as masks had been mandated in Washington state, he “went ahead and went shopping without a mask on that date [the mandate took effect] as a protest.” He was shocked to see the difference one day could make. He was shocked to see so many people complying. “Here and there some people didn’t,” he said. But most were, leaving him with something of a surreal feeling upon encountering the occasional fellow traveler who wasn’t going along with it.

“It was an interesting feeling, kind of like a breath of fresh air and when I felt that, I felt like ‘That is an interesting emotion. I bet I could paint that. That would be a good subject matter for artwork.’ So that’s when I started painting Sanity Her Son and the Credulous,” a work depicting a vibrantly colored woman and her child, unmasked and boldly contrasting with the rest of a dystopian, small-town American street subdued with a muted palette.

“It was just going to be a one-off,” Henderson initially assumed. “I was going to go back to my other work. But before I was even done with that painting, tons of other ideas started to hit me as well. And it was kind of an epiphany. ‘Wait! Why, if I need to be focused on my artwork, but want to protest this, why haven’t I combined the two?’ And I don’t know why it took me a few months to figure that out. But, once I did, I’ve had more ideas than I’ve been able to keep up on painting.”

Patrick Connelly, who was living in Chicago in March of 2020, but now resides in Michigan City, Indiana, was equally skeptical of what was going on in the world around him. He was also working in an industry that was hit pretty hard and pretty fast as the Before Times came to a close.

“I came from a film background. Right after college I went down to New Orleans to work on a medical advocacy feature length documentary called Sick to Death – it’s mainly about thyroid disease and the corruption surrounding that,” Connelly said in a phone interview. “The largest pharmaceutical company who makes medication for thyroid disease is Pfizer,” he went on. “So, I was kind of, you know, primed a few years ago to know how corrupt this company is. And, when I saw that that’s who, you know, was likely going to be the choice [to produce Covid vaccines], I was like, ‘Yeah, there’s nothing scientific about this. This is just gangsters, you know, dominating the world, making billions of dollars.’”

“It was just kind of like a random happenstance,” Connelly continued. “It was just the main editor – me, I was the assistant editor – and the director working in an office together for a whole year. It was very eye-opening and [I] learned a lot about, you know, who funds the medical schools and where they came from and why [they teach] what they teach in them and what they don’t teach.”

Since his stint as an assistant editor on that Sick to Death, Connelly had been working as a video technician and started performing as a VJ under the name Neocord. As a VJ, Connelly creates video content and animations at home, then performs them at live shows and big music festivals, displaying them on large LED screens, ensuring his visuals flow with the music being performed.

Such live shows and big music festivals, of course, were among the first things that had to stop by order of Old Man Fauci – the kids had to turn the music down, get off the big lawns, and go home, often to their parents.

“We were kind of one of the first industries to really feel it when the Ultra Music Festival got canceled…That’s when, you know, everybody started getting laid off,” Connelly explained. “I don’t think anybody really knew how shut down things were going to get, but everyone knew no one was like trying to have social gatherings.”

“So, I lost my job,” Connelly continued. “I went back home [to Maine] for a couple months.”

He took his new girlfriend with him. During that time, Connelly said, “livestreams started becoming a thing where as people couldn’t physically gather, a lot of artists were doing free (or for like donations) livestreams of long events [and] music visuals and that was a pretty good opportunity for me to get my visuals out there.”

During that time, Connelly also did what he described as a “deep dive” into psychology and history to better understand who the people are“pulling all of these strings”.

During that time, Connelly also said he noticed something about many of the other young people around his age and in his industry. “It quickly became clear that for a generation who kind of prided themselves on being…anti-government [and] anti-corporation, it was really baffling to me how quickly all of them fell for the propaganda campaign and it became quickly apparent to me that I was somewhat alone in my industry – that the vast majority of these free thinkers were imprisoned thinkers.”

Connelly wanted to do something through his art to try to open people’s minds. However, he admitted, “I felt like, you know, I was trying to keep my head down as an artist and trying to determine what would be the most effective way to kind of push back and get messages out there that people weren’t hearing or seeing from anywhere else and how to do that basically without getting canceled before I could get my message out to people…I pretty much knew that if, you know, I went too hard too quickly, I would be quickly relegated to the past. I wouldn’t be able to actually perform live anywhere and because VJs are kind of like seen as accompaniments to shows, it would be very easy to replace me…I really enjoy performing and I didn’t feel like I was sacrificing too much by laying a bit more low.”

Even while laying a bit more low, however, Connelly said, he still tried to use his work to point out hypocrisy when and where he could. He decided to take a more active approach in creating animations that hearkened back to things like the Panopticon, as well as the work of social psychologists Stanley Milgram and Phillip Zimbardo, best known for “Obedience to Authority” and the “Stanford Prison Experiment”, respectively.

Reflecting on some of his most current work, Connelly stated, “I’m trying to kind of make animations and still-art that show a definitive pull from some people towards technocracy, towards losing humanity, and showing that that may be packaged in a very beautiful, convenient-seeming package, but ultimately it leaves the world barren and destroys humanity.”

Describing one recent endeavor, Connelly said, “I kind of remixed a clip from They Live and have been putting that into my sets – you know, when he puts on the glasses and it’s like, “OBEY” and stuff like that. I cut in like “Trust the Government,” “Fear Your Neighbor,” just all sorts of these kinds of propaganda things that I want people to really think about.”

He said he’s just trying to drop little red pills. “’[I’m trying] to help wake up these people who are mostly my peers at these shows who I feel I have less and less in common with.”

So far, Connelly said, the reactions he’s gotten to works such as his Panopticon piece and his remixed clip from They Live have been pretty positive. Sometimes his work helps him find people with whom he can connect intellectually.

Yet, many artists who attempt such societal critiques haven’t had as much luck finding public venues to display their work or feel even more restricted in what they’re able to share.

Raging Against Those Who Rage Against the Machine

“We’ve got a pretty vibrant music scene here. It kind of ebbs and flows. We got a population base here and a long enough winter here to produce some pretty awesome music locally,” Tony Mangnall said when asked about his home of Fargo, North Dakota in a phone interview. “I used to play in a couple bands myself and every time there was a show you could get a pretty sizable crowd out to some of the bigger clubs here.”

Although Mangnall still writes and performs some songs he posts to YouTube, mainly to share with friends, Mangnall currently stays busy with a number of other professional endeavors. His main career, he said, is serving as a producer for the televised poker contest, Poker Night in America. Production for the show, of course, was shut down during Covid by order of Father Fauci, who couldn’t have people gambling on TV when we were all supposed to be working to flatten the curve. The show has since “fire[d] back up”, having resumed on August 4 at the Florida Hard Rock Casino. But, while it was shut down, Mangnall said, he worked on a finance livestream and launched a crypto hedge fund that he still manages. On top of all that, Mangnall also does drawings and develops pieces of conceptual art when feeling inspired.

When asked for his views on the current state of art and music, Mangnall put forth some harsh, if not scathing criticisms, distributing blame to both the artists and society.

“I’ve always been drawn to rock music, heavy metal, punk music, because it was dangerous. Scary. Because it was on the boundaries of acceptable behavior. I mean, I liked that part of it that it really shocked people,” he recalled. “And now to see all the mainstream people and all the people who think they’re edgy just go along with Big Pharma and government and the authorities, I mean, this is sickening! I can’t believe it.”

We’ve seen artists and performers censored and attacked before, Mangnall pointed out.

“Like, Lenny Bruce used to get arrested by the cops when he was doing his stand up routines,” he offered as an example. “But there’s something different [now] in that anybody who just wants to do causal art that goes against the mainstream also runs the risk of being called a bunch of bad names and losing their jobs, losing opportunities…[We have] these insane mobs of just childish, cowardly canceling-people [who] will destroy you and just wreck your life if you step outside of their boundaries!”

“I mean, it is really hard to push back because you feel so isolated and that’s by design,” he added.

In Jordan Henderson’s experience during the Pandemic Era, most places refused to touch anything critical of the government, especially with regard to the Covid response.

“I’ve sent artwork in to local papers before,” he explained. “For example, I’ve done like local landscapes, points of interest, and they’ve been willing to publish it. This, they won’t touch.”

But many artists carry on doing the kind of work they want to do, finding available outlets where they can.

Some of Henderson’s pieces have been used in local pamphleteering campaigns he was a part of. “The idea was to use a combination of strong visual artwork to kind of get people’s attention. Draw them in. Make them think a little. And then provide a little information.”

One pamphlet, for example, contained an image from one of Henderson’s paintings, Safe and Sanitized, which depicts a pair of arms, bound at the wrists with handcuffs, holding up a skull against a blue background, the skull being gagged, perhaps choked, with a red mask. At the top of the image, as it appears in the pamphlet, are the words, “Just Two Weeks to Flatten the Curve.”

Many have also turned to getting their art and ideas out to people through alternative and independent media, perhaps without much of a choice other than to conform – which is the option many choose.

One artist who has fully embraced such forums is Ulysses XYZ, the man behind the clown from The Truth Show flier.

In a phone interview, Ulysses XYZ explained,

“If you’re an artist and you’re trying to grow your Instagram following and you start posting, you know, anything that calls into doubt like ‘The Science,’ you know you’re going to be shadowbanned. You’re not going to appear on that list. You’re not going to be in front of those eyeballs. So I think a lot of artists see that and they’re like, ‘Okay, I’ll turn it down. I won’t be explicit about, you know, the idea that mandates for masks [are] just fucking stupid, especially the masks they insist [on] everyone wearing. It was a farce. Everybody should be able to see that. But, you know, if you posted Marilyn Monroe, you know, the Andy Warhol Marilyn Monroe, with like one of those little paper masks on her face, that’s going to get bumped up on Instagram. People see [that] and they’re like, ‘If I make art that aligns with the mainstream narrative, then that will be rewarded.’”

Ulysses XYZ has also witnessed “plenty of people in like in the illustration industry change their opinions because they realized that the art director for, you know, the big publisher they want to work with has these political opinions and if you hashtag the wrong opinion, you’re probably not going to, you know, stay their friend or [on] their list of people to go to.”

“The social credit score has come through social media platforms,” he stated.

Wanting no part in this kind of digital or professional landscape, Ulysses XYZ, has become a big fan of “parallel technologies or technologies that will operate as a platform but [aren’t] owned by Microsoft, by Apple, by Alphabet.”

“I’m kind of at a mental place of frustration where I’m just like, ‘Screw it!’” Ulysses XYZ exclaimed. “I’m going to just make what I want to make and make what I see and poke fun at the fucking bullshit that’s going on. That does not fit with mainstream, you know, platforms. You can’t speak like that.”

At present Ulysses XYZ has several NFTs displayed on and for sale through one such alternative platform, Rarible.

Filmmaker, artist, and host of the Conspiracy Synergy podcast, Teace Snyder takes a similar approach towards his work and its distribution. Much of Snyder’s art can be seen as graphics or animations in videos of his podcast. There are a lot of white rabbits with red pills. There are scientists in biohazard suits. Some deck the merch he sells through his website.

He knows art and ideas critical of Covid, government, and corporations are out there, he said in a phone interview, and he knows what happens to such art and ideas. “[It] doesn’t get disseminated. Or it gets censored. Or it gets shadowbanned. Or it gets tucked under the radar.”

However, Snyder said, in his approach to both his art and his podcast, he has no interest in trying to please algorithms or tech Goliaths. “The question is do you kneel or bend…or do you speak to the truth…”

Snyder chooses to speak what he believes to be the truth. “Will it hurt me in the short term with some demographics?” he asked rhetorically. “Absolutely. Will [my work] ultimately stand the test of time and transcend that initial barrier? Absolutely.”

This approach also allows Snyder to develop his art and his ideas as he pleases.

The development of his art as a form of protest, said Snyder, “[has] been a lifelong thing that has only in the contemporary been accentuated by the authoritarian clampdown surrounding the lockdowns and all of the various different unlawful interventions and how much they’ve hurt people.”

Yet, some artists would argue there’s another component to what’s going on in the art world and its apparent embrace of authority beyond simply overt censorship and the conscious cultivation of one’s politics and art to win favor from angry mobs, corporate art departments, and the all-powerful algorithms of Big Tech.

Ceci n’est pas un urinoir

“I don’t know if you’ve heard of an art piece called Fountain by Marcel Duchamp? Turn of the twentieth century?” Jordan Henderson asked. “What the piece is is it’s a urinal that he [Duchamp] took and put in a show. He turned it on its side and called it a fountain,” Henderson explained. “That’s been kind of an incredibly influential piece within the mainstream art world. A lot of other artists within the mainstream art world have been influenced by it. And I feel like that piece of artwork that Marcel Duchamp put in the show, Fountain, which is this upturned urinal, kind of epitomizes the mainstream world of art, how it is today and how it’s been for quite a while, almost a century. Something like that could literally be put on a pedestal and be put forward as art.”

“So, I feel like the mainstream art world is so into that mentality, right, of accepting something because they’re supposed to,” Henderson continued, “that they would be more susceptible than almost any other segment of society of going along with, you know, a fraudulent pandemic or basically ‘The Current Thing.’ They’ll always go along with ‘The Current Thing.’”

This is something Patrick Connelly had witnessed as well among his colleagues, his friends, and many of the people attending shows at which he performed once everyone was allowed to get together again. He also experienced more direct social ostracism for a period, seemingly because of his divergent views.

Having moved back to Chicago following his time at his parents’ place, but before taking off for his girlfriend’s hometown of Michigan City, Indiana, to escape what he called a “masked-up Zombieland,” Connelly observed with a note of sarcasm, “Most of the friends who I had were Pfizer Gang or Team Moderna, or whatever the kids were doing at the time.”

People he thought were his friends, or at least people he thought he was pretty chill with, unfriended him online or wouldn’t come up to talk with him at shows once he was performing live again. Most of the attendees didn’t seem to mind that they had to be seated at tables and weren’t allowed to stand up to dance or walk around.

“It was some of the most depressing stuff that I’ve ever like been a part of,” Connelly confessed.

“I don’t think [these] people who attended [the shows] were like the daredevils or…[the people] actually awake to what was going on,” he continued. “I think it was like a lot of people who, you know, were told that they were allowed to [attend shows] and so they were being safe because, you know, if they’re allowed to do it, it must be safe.”

As time went on though, Connelly observed, many of these same people changed their views, behaviors, and memories of the past, free from any self-awareness. Those who were clutching their pearls a year earlier at the thought of people risking grandma’s life just to listen to music and dance with others were now posting videos of themselves risking grandma’s life.

“The cool thing,” Connelly stated, “then became to be like ‘Oh yeah, I knew the whole time this stuff was crazy…Oh facial masks are just like decorations? Yeah, like I knew that the whole time.’”

Yet, this level of groupthink and freedom from self-awareness is not unique to the art world or young music lovers. Arguably, it has become a defining characteristic of modern American society.

“People [are] seemingly brainwashed by NPR [and] legacy media,” Tony Mangnall observed. “I’ve [taken] to calling them NPR Americans. I guess another name that other people call them would just be ‘NPCs,’” he added, referring to the abbreviation for “Non-Playable Characters”, a video game term now used to describe presumably human individuals whose opinions and behaviors appear programmed and immutable.

“Every time something came on NPR, there they were repeating it verbatim the next day,” Mangnall continued. “It was astonishing to me to see just the mindlessness with which 60% of our nation found itself in the wake of an alarming election of Trump and in the wake of Covid.”

But this seemingly programmed behavior isn’t limited solely to NPR-listeners either.

“One of the more recent things I’ve been trying to do with my artwork is breaking out of what I consider like the false dichotomy, right, as far as the whole Right-Left dichotomy,” Henderson stated. “There’s a lot of pressure to fall into one camp or the other…I would call it almost like the ‘Patriotic Camp’ on one side and the ‘Woke Camp’ on the other.”

There’s this attitude amongst people, he said, where “if you’re not, you know enemies of one, you’re then assumed to be part of the other. Or, if you do oppose one, then you’re assumed to be part of the [other] one.”

“So, with something like resisting Covid-19 mandates,” Henderson observed, “the stereotype is that it’s very right-wing. Right?” And, to some extent, in some places, that reputation has been unfortunately earned, he explained. “I’ve attended protests where, for example, [the] protest will open with flag ceremonies.”

What struck Henderson about this, he said, was how similar these “flag rituals” were to the masks, as both constitute a pressured, if not coerced, expression of symbolic behavior.

“So that’s why I did a piece called Eclipsed,” he said. The piece depicts a middle-aged, middle-class, masked American standing before a cross, pledging his allegiance to an American flag with a skull and crossbones in place of stars.

“I tried to make a painting like that to maybe kind of make people on the Right think too about what they’re doing,” Henderson said. “Because to me, I feel like they’re undermining their own position. They’re saying the government’s not trustworthy…but then they have almost a worship of the government at the same time.”

At present, Henderson added in mid-July, he was “working on another painting to criticize the Left for basically the same thing.”

“I’m focusing…trying to basically show the hypocrisy within the positions on both the Right and the Left, and kind of how ridiculous this false binary is,” he explained.

To some though, this false binary is more than ridiculous – it, in reality, has the potential to be devastating to our way of life.

For 20 years Steve Henderson, the father of Jordan Henderson, worked in a corporate position as a medical and general illustrator. When Steve was in his fifties, his position was downsized. According to a written statement from his wife and business manager, Carolyn Henderson, Steve saw this coming though and had been building his fine art presence on the side.

According to the statement from Carolyn Henderson, one particular source of inspiration that has always struck a chord and served as source of inspiration for Steve Henderson was the story of the indigenous people of North America.

“Many of the tribal groups were enemies of one another, and rather than join together to combat the common enemy of the US Government, they let factions grow, to the point that some groups would work with the US Army against other groups. The divisiveness reminds Steve of the whole Democratic/Republican, Conservative/Liberal paradigm, splitting people apart so that we fight with one another, as opposed to standing against the overlords,” the statement read.

The Truth Is Out There

“I honestly don’t really know of any galleries that are exclusive, Truth-based, or kicking-back-against the-system-galleries,” Jeff Madeen thought aloud in mid-July, a couple weeks after opening night of his Truth Show, which would run through the end of the month. “I guess my gallery because I have a room [that] just has my work in it. My work [isn’t] 100% exclusive truth-based art. But it’s probably 80%.”

There are a number of reasons for this, he suggested. “At the very top of the art world, it’s very corrupt. It’s corruption between the artists, the galleries, the auction houses, and the museums. How do you value art? Right? I mean, it’s what anybody’s willing to pay for it. So there’s a fair amount of money laundering that happens at the very top of the art world.” The art used for these purposes though, usually isn’t the art doing the hard-hitting questioning.

Galleries are also under a lot of pressure from their collectors to display and sell what is fashionable amongst the collectors which can be influenced by what is going on at the top and in other corners of society. Presumably, if collectors want more urinals, galleries will display more urinals.

That said, Madeen also admitted, “Truthfully [Truth art] doesn’t sell.”

“For instance,” he said, “my wife’s opinion would be ‘I don’t want to surround myself with that stuff. That’s not comfortable. That’s not pretty. That’s not whatever.’”

But Madeen still likes the concept. “I [want] people to think. You know, people need to think and they need to, you know, maybe get hit across the side of the head with a two by four – you know, hard-hitting art.”

Thus, Madeen put the word out that he was looking for artists to submit works depicting that ideal. “My goal was to get Truth artists to, you know, actually make a comment on this time that we’ve been going through.”

In total, Madeen estimated he accepted approximately 117 works by 50 artists that he would display and try to sell in his gallery throughout the month of July following the big opening on the night of the first.

“There were some extremely hard-hitting don’t-pull-any-punches kind of art and then there were, you know, other pieces that in my estimation really had not a lot to do with those subjects,” Madeen noted.

Jordan Henderson was definitely among those to take the call for Truth and commentary seriously, as was his father, Steve Henderson. Jordan had three pieces on display at The Truth Show. Steve had two. Both made a point of heading down to Pueblo from Washington for opening night despite some car troubles.

Ulysses XYZ was there too with some NFTs. Tony Mangnall brought a few works of his own, as well as his girlfriend. Teace Snyder had what he described as five “tiny things” there, “individual things for purchase,” “little pieces of work done for show.” Unfortunately, however, Snyder was unable to make it because he’s in Canada. Patrick Connelly wasn’t able to make it either.

Despite having several pieces of his own works on display, being scheduled to be part of a performance, and being the host, Madeen wasn’t really able to partake in the evening either. Ironically, he came down with Covid just before the show and wasn’t feeling up for doing anything more than briefly coming down from his loft to greet a couple of good friends.

For those who could enjoy the evening though, that night there was a band and some performance pieces. Those who were there noted the building was packed and estimated that perhaps several hundred people circulated through over the course of the night.

“[People] got exposed to, you know, types of art that they probably wouldn’t get exposed to,” Madeen said. From what he could tell, “A good time was had by all.”

Jordan Henderson observed, “[There was] a very broad range of people. You know, people who saw through Covid [and] were awake to it and other people who were even still wearing masks but were open-minded enough that they were willing to come and look at the artwork.”

Like many events in the Pandemic Era, there were several Covid rules artists and attendees were expected to follow though.

A set of behavioral expectations written by one of the people who helped Madeen organize the event explicitly stated, “If you must, you can wear a mask at the opening, but this will be to protect yourself. You cannot expect other people to wear a mask to protect you. This simply would not be in alignment with the theme of the show ‘Truth,’” and “You will be expected to stand within 6 feet of other people, hug them, laugh and talk to them.”

Ulysses XYZ noted, “Jeff put together a bunch of great artists that are all about, you know, liberty is worth fighting about and calling out censorship and restrictions and authoritarian nonsense.”

“You should be able to call that out and I really appreciate that about the whole Truth Show,” he added.

Whether the event had any real impact on broader society, however, may be unlikely given the enormity of such a feat. Whether it opened any minds or brought anyone together, is difficult to say. A single Truth Art show can only do so much.

When Madeen was interviewed in mid-July, he said he was working on compiling a book containing high-quality images of all the work that was displayed, “So that can maybe spur on people for next year.”

“Once people kind of [see] the show and what people did, I think they’ll get inspired to maybe be a little bit more truthful,” he added. “Not that they’re lying,” he was quick to clarify. “But [no one is] challenging people to think hard enough.”

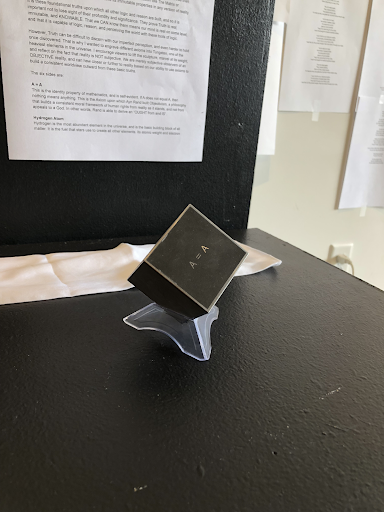

Of all the pieces that will be contained in that book, of all the pieces displayed at The Truth Show, one that truly takes Madeen’s challenge to heart is a conceptual piece titled Axiom by Tony Mangnall.

“We just have people essentially watching two different movies,” Mangnall said. “They can look at the same footage and come away with completely different conclusions.”

“It’s easy for people to assume that truth is completely subjective and that it is whatever our perception makes it out to be,” he continued. “I find that to be lazy philosophy. A lazy understanding of Truth and our ability to observe it. I believe that Truth is not subjective. I believe it is objective and that we are merely subjective observers of an objective reality and that sometimes we get that observation wrong because our capacity to observe it is hindered by our own issues, our own weakness as humans.”

“[However], there are Truths out there that we can agree on no matter what,” Mangnall expounded. “Those Truths are called axioms and those are represented by things like mathematical equations or the fact that a triangle has 180 degrees in its internal angles. That’s true no matter what. If that’s not true then you’re just not talking about a triangle. No matter who’s observing it. No matter who’s perceiving the triangle, or whether even there’s a universe or consciousness there to perceive it. Those are the immutable facts about a triangle.”

This is what Mangnall set out to convey through Axiom, a two-inch tungsten cube in which he engraved immutable truths such as “A = A,” a hydrogen atom, an equation for orbital mechanics, the golden ratio, and a QR code that takes the owner to the work’s NFT which contains a file to prove ownership and authenticity.

The reason he chose tungsten, Mangnall said, was because “it is astonishingly dense and astonishingly heavy.” Those who grasp Axiom, he said, are astonished at the weight of this two-inch cube and how difficult it is to handle.

“It weighs well over six pounds,” explained Mangnall. “When you look at it, it doesn’t seem like it would ever weigh that much. So, I like that because Truth can often be hard to handle. Hard to hold. But for those that are capable of doing it, you have access to what I believe is a consistent understanding of the universe that helps you also to navigate downstream when the world starts getting weird.”

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.