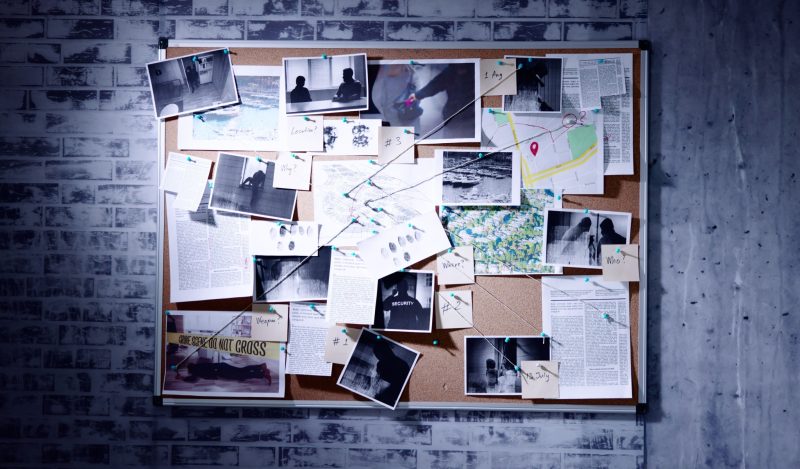

On November 20, Arizona’s Attorney-General Mark Brnovich alleged that Maricopa County, the state’s largest, broke the law on Election Day when 25 percent of vote tabulation machines malfunctioned. Katie Pavlic reports that “The issues detailed by Brnovich could inhibit the ability to lawfully certify the 2022 midterm election results.”

Does this explain why by November 21, the state’s gubernatorial election had still not been determined, with the difference in tallies between Katie Dobbs and Kari Lake being tantalizingly close—0.67 percent—to the 0.5 percent margin that would automatically trigger a recount? Except, what would be the point of a recount instead of a redo of the election itself? And what if any other results for the Senate and House were also affected?

As of the same date (November 21), four House results also were yet to be called. And it took several days for the race for control of the Senate to be decided as well.

The US presidential election is the most internationally consequential of all and hence of immense professional interest to a student of global affairs and democracy. Yet, it’s hard to see that US elections would pass the test of UN-certified international best practice of free and fair elections.

The gold standard for “free and fair” elections is the secret ballot in a secure setting, free both of coercion and of opportunities for rigging votes and counts. US elections are anything but. Mail voting has expanded enormously but, along with ballot harvesting, is more vulnerable to mistakes, manipulation and tampering than in-person voting in designated polling stations with scrutineers from all parties to observe voting and counting.

Postal voting can expand voter turnout as people can more easily vote at a time and in the manner of their convenience and choosing. But if postal votes are cast in big enough numbers to determine individual and overall party seats, then all states need to pay far more careful attention to safeguards to ensure the integrity of process and legitimacy of outcome.

Trump lost in 2020 by a mere 44,000 votes across three states. The system makes it difficult to detect and defeat strategic voting of harvested ballots in individually targeted polling centers.

A Rasmussen poll near the end of September found that 84 percent of Americans expressed concern about election integrity in the imminent congressional elections. By a 62-36 majority, they held eliminating “cheating in elections” to be more important than “making it easier for everyone to vote.”

There are multiple pathways through which, and multiple points at which, the machinery can be corrupted. This begins with how the ballots are mailed out, to whom and at what address, verification of voter identity, how the votes are received, stored and counted, and what other steps are taken to prevent tampering, interference, padding with phantom votes, and illegal invalidation.

Covid restrictions gave Democrats the opportunity and alibi to dramatically expand the menu of voting to include mail-in votes, universal absentee ballots and unmanned (or should that be unpersoned?) drop boxes. With only a little more than half of votes cast on the day and the outcome delayed for several days after, it’s no longer accurate to refer to Election Day.

The easily corruptible system is here to stay. Republicans had better smarten up their act and get down and dirty to engage in ballot harvesting instead of complaining about it in each successive election. By joining the fray, Christopher Bedford argues, Republicans will level the playing field and, if they start winning, bipartisan support could grow to clean up the electoral system to the benefit of US democracy.

This is not to imply by any means that constituency gerrymandering, and questionable voting practices are restricted to Democrats. Rather, the big picture here is that regardless of which party wins, the loser is American democracy with declining trust in the process and the legitimacy of the president, Senate and House.

CNN reported that exit polls from this year’s midterms show that 35 percent of Americans believe that Biden’s win in 2020 was not legitimate. Unsurprisingly, Republicans make up 93 percent of the sceptics. In addition, similarly, of the 19 percent who harbor doubts about fairness of their state elections, 80 percent are Republicans. This is not good either for the health of US democracy or for US leadership of the “free world.”

Proving electoral malfeasance to an appropriately rigorous standard in a court of law, however, is an extremely tough ask. Statistically improbable results and anomalies in critical precincts will rarely cut the mustard as a legally acceptable standard of proof of malfeasance.

The world’s oldest and most powerful democracy could learn much from the world’s largest democracy on how to do elections.

India has the world’s most efficient, effective and credible election machinery. The Election Commission of India (ECI) does a brilliant job of organizing and conducting elections, counting votes and certifying results under the most challenging of circumstances. With the introduction of electronic voting machines in this century, the outcome is known in a matter of hours and almost all individual results are known on the same day.

In the US, by contrast, until the turn of the century, we would know the overall House and Senate outcomes on Election Day but now we wait, and wait, and wait.

India’s last federal election was conducted in seven staggered phases from April 11–May 19, 2019.

The reason for the staggered voting, and a comment on the ECI’s immense professional competence, organizational skill and integrity, is the sheer scale of the exercise. The ECI is vested with enormous powers to organize and conduct national and state elections, recognize political parties, establish procedures for the nomination of candidates, and register all eligible voters. It also has the responsibility to delimit all the parliamentary and state assembly constituencies, which of course takes away opportunities to gerrymander constituencies to favor the party in power.

The numbers are wearisome: 912 million eligible voters (an increase of 83 million since 2014); over one million polling booths; around 1.5 million electronic voting machines; over four million election personnel; and two million-plus police officers to oversee security.

The biggest constituency had three million people. Counting of the more than 600 million votes that were cast (representing a 67 percent turnout) began and was concluded in one day on May 23. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) was confirmed as having won 303 of the 545 seats in the Lok Sabha (the lower House), up from 282 in 2014.

The ECI announced the poll schedule in early March. Let me repeat that. The ECI, not the prime minister or the government, announced the dates of the election, although the government still chooses the date on which a current Parliament’s term ends. This takes away, not all but certainly one important advantage of incumbency. The ECI also drafts a Model Code of Conduct that kicks in as soon as the election schedule is announced. This governs the entirety of elections, from political speeches and rallies to manifestos, polling booths, general conduct and social media.

The ECI is a constitutional office with correspondingly elevated status, authority and importance. The Chief Election Commissioner is given security of tenure on par with the judges of the Supreme Court of India.

Not one of the many federal and state elections since 1950 has had the overall outcome questioned. This is not an assertion that can be made of the US with any degree of plausibility.

Of course, with vastly greater emphasis on states rights in the US federal constitutional structure compared to India’s, the ECI machinery cannot simply be transposed across from one context to the other. That is not the argument being made.

Rather, what is suggested is the need to eschew provincialism and consider how best to adapt India’s proven advantages in conducting elections to the US context, perhaps with the establishment of independent state election commissions. For in the long term, the fate of democratic polities and free peoples may hinge more on US electoral reform than on the outcome of particular elections.

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.