Last year, the Australian Government’s proposed legislation to combat misinformation and disinformation was shot down in flames after a strong backlash over the threat to free expression, and the unfairness of special exemptions for government and media.

Critics complained that the bill would result in the censorship of a staggering range of speech, on issues from the weather, to scientific debate, to elections, to religion, and public health.

The government shelved the deeply unpopular bill, promising to take on board concerns raised in over 3,000 submissions, and a further 20,000 comments made to the Australian Media and Communications Authority (ACMA) during its consultation phase. For context, fewer than 100 submissions were made during consultation on Digital ID legislation.

Today, Communications Minister Michelle Rowland tabled a new version of the bill which she said is intended to “carefully balance the public interest in combatting seriously harmful misinformation and disinformation with the freedom of expression that is so fundamental to our democracy.”

The new bill includes strengthened protections for free expression, with exemptions for satire, parody, news content, academic, artistic, scientific, and religious content.

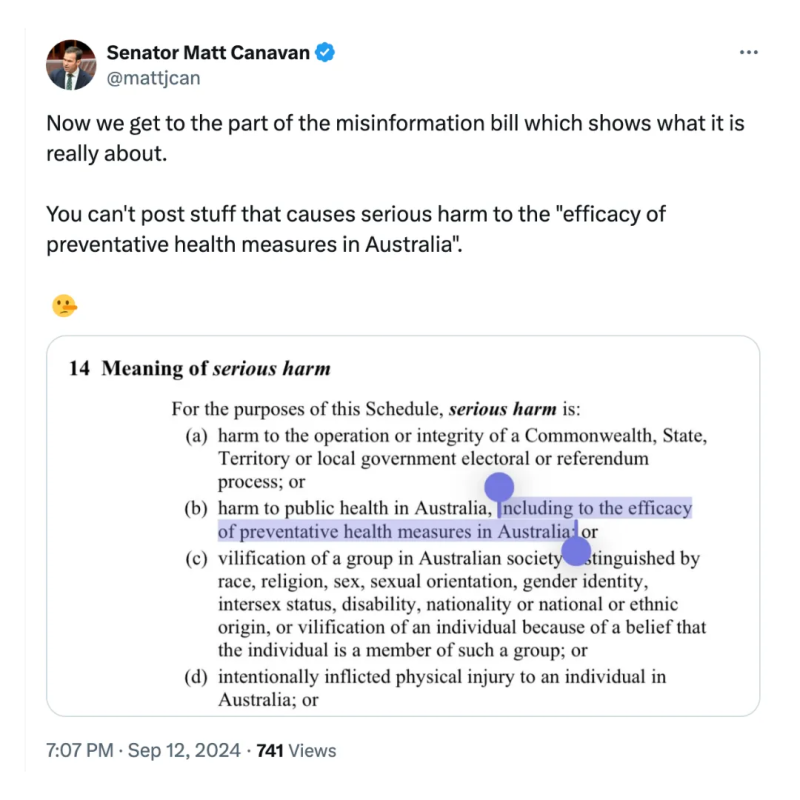

The previously overbroad definition of harm arising from misinformation and disinformation has been narrowed, with the qualification that harms must be “serious” and “imminent,” with “significant and far-reaching consequences” for the public, or “severe consequences” for an individual.

Definitions of misinformation and disinformation have also been brought into closer alignment with industry definitions such as “inauthentic behaviour” (e.g.: bot farms) and requirements for misinformation to be “reasonably verifiable as false, misleading or deceptive.”

Content disseminated by the government will no longer be exempt from the laws, although professional news organisations regulated under other legislation and industry codes will be exempt.

As in the previous version of the bill, the ACMA will not police content or individual accounts. Rather, the ACMA will take a “systems-based approach” to holding digital platforms to account by enforcing transparency and adherence to an industry code.

However, experts say that despite the revisions, the bill is fundamentally flawed and will become a political tool to advance government objectives and quash dissent.

Flawed Foundations

Graham Young, director of non-partisan think tank the Australian Institute for Progress, and my co-author on a paper (in progress) examining the research underpinning the government’s misinformation bill, said that the bill can amount to nothing more than a “shoddy attempt at censorship” because it is premised on flawed understandings of misinformation and the discursive process.

“It’s essential for the functioning of a modern society that information be freely available and freely discussed,” he said.

“Inevitably, especially in situations of emerging information, there is going to be a lot of misinformation, whether deliberately or by accident. That is a benefit.”

“Misinformation is essentially a hypothesis that is wrong. Knowledge advances by testing and discarding hypotheses. But most hypotheses aren’t completely wrong, so testing them can provide knowledge that would otherwise not have come to light.”

Interfering in the discursive process would be problematic enough even if all misinformation could be eradicated from the internet, but the government’s own documentation supporting its bill proves that it’s an impossible pursuit, even for qualified ‘experts.’

“Re-examination of the data from [the research underpinning the bill] shows that what is misinformation yesterday is often fact, or close to, today, and it calls into question the government’s whole rationale for this intervention,” said Young.

Indeed, in a key study of misinformation commissioned by the ACMA, Canberra University researchers incorrectly classified posts about vaccine mandates and the lab-leak theory as misinformation, but vaccine mandates were introduced months later, and the lab leak is now widely thought to be equally or more likely than the zoonotic origin theory.

Moreover, the researchers coded respondents who thought that authorities exaggerated the risks of Covid, or who questioned the efficacy of masks or the safety of Covid vaccines as “misinformed.” Yet it is now accepted that authorities wildly overestimated the risk of Covid – the World Health Organisation initially reported a 3.4% risk of death, compared to the real risk in 2020 of closer to 0.05% – and there are hundreds to thousands of peer-reviewed scientific papers questioning both the efficacy of masking and the safety of Covid vaccines.

Based on the best available evidence to date, it appears that the respondents who the researchers categorised as “misinformed” were in fact better informed than those who were categorised as “informed,” while the latter were simply those who believed everything the government said at the time.

The Politicisation of Misinformation and Disinformation

Twitter Files journalist and director/founder of digital civil liberties initiative liber-net, Andrew Lowenthal, agrees that the revisions to the government’s misinformation bill only make it marginally less bad.

“On some level it is an improvement, but that’s a low bar because the previous bill was so terrible,” he said, noting that one of the key underlying problems of the legislation remains, which is the (currently) voluntary industry disinformation code that the new laws will extend and enforce.

The code requires that digital platforms employ a range of moderation tools including the labelling, removal, deamplification or demonetisation of false and misleading content, and the suspension of accounts engaged in inauthentic behaviours.

This activity is to be supported by “prioritising credible and trusted news sources,” “partnering and/or providing funding for fact checkers to review Digital Content,” and co-ordination with government regulators.

These are obviously flawed methods for sorting true from false information. “Credible and trusted news sources” routinely publish falsehoods without making follow-up corrections, and fact-checkers frequently make false and biased claims which amount to no more than opinions in a court of law. Platforms using official policy positions as a proxy for ‘truth’ ensure strict adherence to political policies but automatically filter out emerging science and thought.

Through his reporting, Lowenthal has documented the weaponisation of these industry standards by governments to censor dissent, showing that, given enough rope, governments will claim a monopoly on ‘truth’ for political ends.

“Governments are political operators and will have a tendency to employ all the tools at their disposal to make their political view dominant,” said Lowenthal.

Lowenthal has reported on the Australian Government’s role in flagging content, some true and some memes, for takedown by X, then Twitter, to stifle public dissent during the pandemic.

More recently, he reported on Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s admission that the Biden administration and three-letter agencies had aggressively pushed to censor Covid information, some of which was true or satirical, and the Hunter Biden laptop story, which also turned out to be true.

Ironically, the idea that the true Hunter Biden laptop story was supposedly disinformation was itself a disinformation campaign seeded at an ‘anti-disinformation’ prebunking workshop run by the Aspen Institute, which was attended by key figures from digital platforms and reporters from trusted news outlets, including the New York Times and the Washington Post.

At the workshop, attendants rehearsed how to suppress the laptop story, two months before the New York Post broke the story in the heat of the 2020 Presidential election campaign. Polling suggests that at least some Democrats would have changed their vote had they known the story was true, which by the Australian misinformation bill’s definition, could constitute disinformation that caused serious harm to electoral integrity.

In turn, one of the participants in this ‘anti-disinformation’ workshop was Claire Wardle, former head of the now defunct anti-disinformation group, First Draft, which was a key partner in shaping the industry disinformation code that the Australian Government’s misinformation bill will extend and enforce.

If this is reading like the synopsis of Inception, that’s because the ‘anti-disinformation’ network of NGOs, academic working groups, think tanks, and government agencies is prone to all the same problems of politicisation, vested interests, bad research, and corruption as any other industry.

The point is this: Systems designed to combat misinformation and disinformation are easily gamed by political actors to achieve political ends.

No Robust Safeguards to Prevent Censorship of True Information

I asked the ACMA how it will ensure that the wrong information (i.e.: true information) will not be demonetised, deamplified, or removed by overzealous platforms eager to comply with the new misinformation laws under threat of financial penalties of up to 5% of global revenue.

A department spokesperson responded to assure that the tightened-up definitions of misinformation and disinformation provide “a high bar,” meaning that the bill “only applies to content that results in certain, defined serious harms to Australians.”

However, ABC reports that Rowland suggested that the new laws will cover, for example, content that urges people against taking preventive health measures like vaccines, so what is a high bar for the ACMA may be scraping the ground for others.

The spokesperson added,

Platforms will also be expected to be transparent with Australians on how they treat misinformation and disinformation. The Bill requires them to publish their policy approach to misinformation and disinformation as well as the results of risk assessments relating to misinformation and disinformation on their services.

The ACMA will be empowered to register codes and make standards and this would be subject to protections around freedom of political communication, as well as Parliamentary scrutiny and disallowance.

It is pleasing to see that the ACMA will require transparency about how misinformation and disinformation are “treated,” and that the enforced industry codes will include protections for political communication. However, this offers no insight into how platforms will ensure that true information does not get caught in the net.

This is especially pertinent since Labor Government politicians have recently taken to calling any political communication they disagree with “conspiracy theories.”

I also asked what rubric the ACMA will use to determine the degree of harm caused by misinformation and disinformation.

In a report explaining its rationale behind the first draft of the bill, the ACMA previously offered three case studies of how misinformation causes harm, but only one case study, on anti-5G content, demonstrated harm arising from misinformation. The other two case studies included factual inaccuracies (i.e.: misinformation), or failed to demonstrate harm.

The department spokesperson responded,

The ACMA would have record keeping powers to enable it to gather consistent and comparable information across platforms, which would allow them to form an evidence base (including key performance indicators) to benchmark the effectiveness of platforms’ efforts to address mis- and disinformation.

I am not convinced that the department liaison understood the assignment on this question.

Not All Laws Are Good Laws

The revised misinformation bill is just one of a slew of legislative solutions put up by the government in recent weeks to address problems relating to social media, online activity, and speech.

This week alone, the government committed to legislation imposing social media age limits to protect children online, criminalising doxing, new privacy reforms, and new hate speech laws.

The intentions behind all of these bills may be noble. In a parliament today, Rowland said that harms arising misinformation spread in the wake of the Bondi stabbing earlier this year and the UK riots were examples of why this new bill is needed.

Undoubtedly, some of these reforms are necessary and helpful. However, the new misinformation bill is not one of them.

“The absurdity of the government’s legislation has recently been demonstrated by the fact that the Labor Party established a site for reporting misinformation, and it was swamped with people using the government’s own propaganda as examples,” Young noted dryly.

While the shadow Communications Minister David Coleman strongly criticised the draft misinformation bill last year, Opposition leader Peter Dutton more recently said that he was “happy to look at anything the government puts forward.”

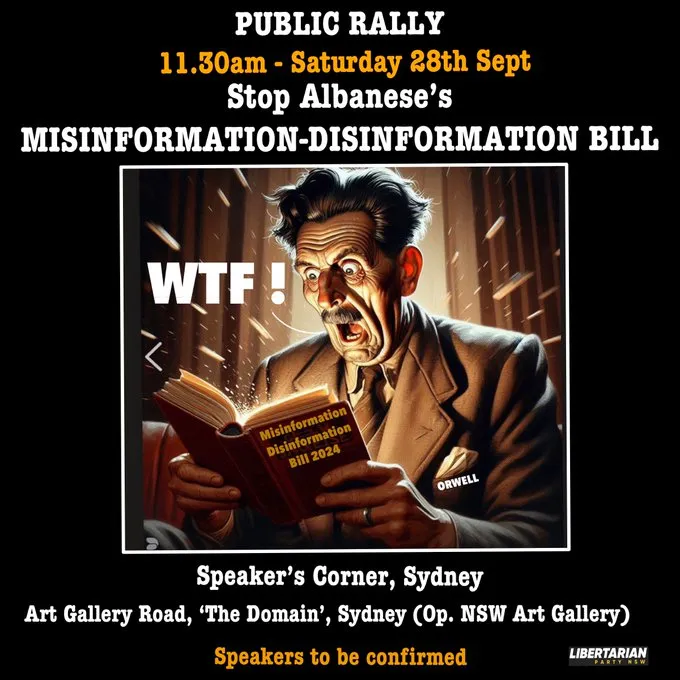

New South Wales Libertarian MP John Ruddick called it the “most insidious bill since Federation” on X today, and is organising a public rally in Sydney to oppose the bill at the end of the month.

The parliament will debate the misinformation bill at a future date, and the government hopes to pass the bill into law before the end of the year.

Republished from the author’s Substack

Join the conversation:

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.