Early in the pandemic, we rejected ‘herd immunity’. Perhaps the word ‘herd’ conjured ideas of animals led to slaughter, a dehumanising mass culling. This rejection followed a BBC interview with David Halpern, the head of the UK government’s Nudge Unit:

“There’s going to be a point, assuming the epidemic flows and grows, as we think it probably will do, where you’ll want to cocoon, you’ll want to protect those at-risk groups so that they basically don’t catch the disease and by the time they come out of their cocooning, herd immunity’s been achieved in the rest of the population.”

This was a fairly innocuous comment, but it drew fire in the media. Although the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care, Matt Hancock, claimed that pursuing herd immunity was never the UK government’s policy, it is unlikely that Halpern, close to Number 10, would have spoken out of turn. Herd immunity may or may not have been ‘policy’, but it is an end result of a pandemic nevertheless. It occurs when a large enough percentage of the population is immune that it becomes difficult for a virus to spread. The population finds itself in a state of détente with the endemic disease. In the absence of vaccines, herd immunity would be reached solely through infection-acquired immunity. Both combine to form ‘hybrid immunity’.

When we angrily refused the idea of herd immunity, we offered ourselves up on the altar of behavioural science to herd psychology. Unable to face one fact of nature, we made ourselves blind to the exploitation of our own nature.

The government was nervous that the population would not follow the draconian lockdown rules and posed a question to the SPI-B advisors: “What are the options for increasing adherence to the social distancing measures?” And this is when SPI-B famously recommended that

“the perceived level of personal threat needs to be increased among those who are complacent, using hard-hitting emotional messaging.”

As one of those SP-B advisors told me anonymously,

“Without a vaccine, psychology is your main weapon.You have to restrict ways in which people mix and the virus can spread… You need to frighten people.”

This essay is about the tension between the individual and the collective, i.e. the herd. I have found myself thinking about human nature, individuality, the collective, the leaning into authority and the totalitarianism which has bubbled up over the last two years.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn said the line separating good and evil runs through every human heart and he believed it would never be possible to expel evil from the world, but that we should constrict it within each person as far as we are able. Hannah Arendt came to the same conclusion: “The sad truth is that most evil is done by people who never make up their minds to be good or evil.”

The word ‘evil’ has religious or supernatural overtones which people can find off-putting. At various times, ‘unnecessary cruelties’ or ‘mal-intent’ or ‘foolishness’ will suffice, but I think you will know what I mean as I continue to use the word ‘evil’ alongside substitute words.

We are what our consciousness knows of itself. If we regard ourselves as harmless beings then we are foolish as well as cruel. When the pandemic is done, some will brush off the harms inflicted during the response to Covid with an embarrassed laugh. They might pretend that they were never part of it. New high ground will be sought in hindsight. The danger that follows is in conveniently relapsing into a woolly-headed collective amnesia. But evil deeds do not belong in the past, they are our present and our future, and this is why it is essential to consider why it is in our nature to perpetuate cycles of foolishness and cruelty.

Recovery and healing should be accompanied by misgivings about what we have done, the prickle of conscience and desire to do better. This goes beyond any (whitewashed and late) inquiry into government response, it is a duty and of benefit to the individual as well as society. As Carl Jung said, “None of us stands outside humanity’s black collective shadow.”

Fortunately during Covid we have not endured the depth and scale of the horrors inflicted by Stalin, Mao Zedong or Hitler. Countries battled through a virus as best they could, but there were penalties, cruelties and mistakes. Remarkably, we traded liberty for a sense of security (the transactional value was never guaranteed) and criminalised activities which should be far beyond the interest of the law or government. Children were deprived of education. Women birthed alone. People died alone. Jobs and businesses were lost. Much of this was not necessary, and was not included in previous pandemic plans for good reason. Bodily autonomy and freedom of medical choice were nearly forsaken. In the developing world the consequences were devastating and even more out of scale with the threat.

An abundance of headlines show how far the ‘othering’ of non-compliant unvaccinated people went. None put it so clearly as Polly Hudson in the Mirror:

“Get jabbed, or else. It sounds harsh – and it is – but the time has come where it’s essential. Because we’re on our own now.

The vaccine hesitant – those who are afraid, because they’ve genuinely fallen for untrue propaganda – need to be persuaded. The militant, rabid anti-vaxxers will never be persuaded, so they need to be forced.

The unvaccinated must become social pariahs.”

The ‘jabs for jobs’ crisis has been averted here in the UK. Vaccine mandates appear to be relaxing or dropping, country by country, but the threat was real, and may yet re-emerge. At what point do we sit up and take notice? When do we say, this is not quite yet totalitarianism, but it is a beginning. Solzhenitsyn put it well when he said,

“At what exact point, then, should one resist? When one’s belt is taken away? When one is ordered to face into a corner?”

In the UK, lockdown was enforced under the Public Health Act, originally designed to immobilise and treat people who are infectious, not the entire population. Laws, as well as moral pressure and social coercion (exacerbated by a deliberate behavioural science approach) created an atmosphere of almost complete compliance with lockdown, and the associated cruelties, which were posited as being for the greater good.

The personal sacrifices made by millions of people during this pandemic have been colossal.

— The Labour Party (@UKLabour) January 13, 2022

We haven’t forgotten. pic.twitter.com/DP4LoGmJPa

Astonishingly, the UK Labour Party shared a quote by a nurse saying that she had refused to let a man be with his dying wife, for “the greater good”. The intention was to shame the Conservative party for ‘Partygate’, but instead it revealed how morally adrift and lacking in compassion people became. Jenny followed the rules, but maybe she shouldn’t have.

Research shows that authoritarian governments are more likely to emerge in regions with a high prevalence of disease-causing pathogens. We can also deduce that at a deep level, there is an impulse in at least some people to be taken care of by the state, to be relieved of the responsibility of deciding how to behave in troubled times. In the early days of the lockdown, Boris Johnson assured the nation that the government would put its arms around every single worker. Despite being well-meant, this could evoke comfort or a stranglehold, depending on your perspective.

We have experienced a very unique combination of circumstances: fear of infection, the deliberate amplification of fears to induce docility, and isolation caused by lockdowns. The effects of the constant fear and threat messaging have manifested themselves in harmful ways, such as obsessive hygiene habits, compulsively checking for symptoms or a fear of public transport. These and other maladaptive behaviours characterise Covid-19 Anxiety Syndrome. 47% of the British people suffered moderate to severe depression or anxiety during the first year of the pandemic in a studyconducted by Professor Marcantonio Spada at London South Bank University. This was the highest of any country in the study and three times the normal level for the UK.

This state of fear, lockdown and isolation created a crucible for authority and compliance, but also for mass hysteria.

Professor Mattias Desmet has put forward the theory that the world is experiencing ‘Mass Formation Psychosis’. He says that people are in some sort of group hypnosis, which was enabled by pre-existing conditions, including free-floating anxiety and frustration, life experienced as meaningless and a lack of social bonds.

His theory has been disputed and fact-checked. (Like everything that goes against official public health guidance.) It seems a difficult theory to evidence. For instance, can we prove that Nazi Germany experienced mass hysteria? There were complex group dynamics at work, the nation was not uniformly ‘hypnotised’, yet researchers have studied how Hitler used the media for propaganda purposes and to control the population. I suspect whether you gravitate to Desmet’s theory is as ideological and personal as whether you like the idea of the government putting its arms around you. I shared my own intuition in A State of Fear that we have been in a time of mass hysteria.

Desmet’s theory appears to be foregrounded by the work of Arendt, Gustave Bon and particularly Carl Jung, who first coined the term ‘mass formation’. He lived through the destructive collective movements of the world wars and the Cold War. What he said then about mass movements, and the ‘shadow’ in our psychology might apply to what is happening in the world now.

Mass hysteria, mental contagions and psychic epidemics happen when masses of people are caught up in delusion and fear – the sorts of situations which have been stirred up by evil leaders in our recent history. Fear during an epidemic is natural, but the amplification of fear (even if supposedly in our best interests) may have blown bellows on dry tinder. A vicious circle is created as fear makes people irrational and lean more heavily on government advice; irrational action leads to negative consequences; and negative consequences lead to more fear.

According to Jung,

“[psychic epidemics] are infinitely more devastating than the worst of natural catastrophes. The supreme danger which threatens individuals as well as whole nations is a psychic danger.”

In his book, The Undiscovered Self, he offered advice about how to minimise the risks to the individual and to society.

“Resistance to the organised mass can be effected only by the man who is as well organised in his individuality as the mass itself.”

Individuality is a dirty idea in a time when the collective good and solidarity are extolled. We were told to wear masks for others, if not ourselves. This and other solidarity-based messaging stemmed from the advice of behavioural scientists that appeals made to the collective conscience are more effective than appeals based on the threat to ourselves.

Can we balance concern for the whole of society with individuality? It’s important to understand that Jung meant we should self-individuate, not be selfishly individualistic. Furthermore, self-individuating offers all of society hope, if it helps to avert the psychic epidemic.

He put forward that we self-individuate through finding meaning. One way is to choose to find “a new interpretation appropriate” to our current situation “in order to connect the life of the past that still exists in us with the life of the present, which threatens to slip away from it”. We can forge opportunity from calamity.

Meaning can also be derived from social connections, religion and work, according to Jung. Life has arguably become more atomised, and this was exacerbated during lockdowns. The danger is that the more unrelated individuals are, the more consolidated the State becomes, and vice versa. Jung did not believe that the mass State had any intention or interest in promoting mutual understanding and the relationship of man to man, but rather strived for atomisation and the psychic isolation of the individual.

The use of modelling during the Covid epidemic mirrors and builds upon Jung’s theory that scientific rationalism adds to the problematic conditions which can lead to mass hysteria:

“…one of the chief factors responsible for psychological mass-mindedness is scientific rationalism, which robs the individual of his foundations and his dignity. As a social unit he has lost his individuality and become a mere abstract number in the bureau of statistics.”

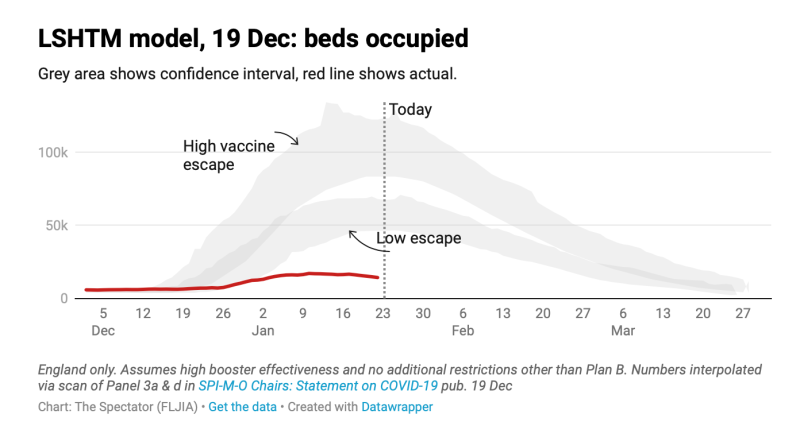

The doom-mongering modelling which catalysed lockdowns does, by its nature, treat humans as social units. But by depriving us of individuality the modelling also deprives itself of accuracy. Professor Graham Medley who chairs the modelling group SPI-M reported to MPs that it is impossible to predict human behaviour and therefore the most pessimistic outcomes were offered to government. Perhaps the humanities (excepting behavioural science which also treats people as social units) should have been weighted equally with modelling in the decision-making in order to avoid such gargantuan errors in forecasting.

The most meaningful social interactions and vital human rites – birth, marriage and death – were interfered with by lockdowns and restrictions. Banal encounters were also paused for weeks and months at a time. Individuals and families at home were isolated social units and more vulnerable to fears and, potentially, ‘mass formation’. This follows long-standing trends in our culture towards isolation and anxiety. Professor Frank Furedi has written extensively about the culture of fear and how we got here.

Gazing forwards, how much more prey might we be to the mass State and mass hysteria in the future of ‘untact’ versus contact cities? An isolated way of life may become more normal in ‘smart cities’ which utilise technology to promote efficiency and manage urban flow, including human ‘social units’. Untact cities (Seoul in South Korea is the blueprint) aim to reduce human contact by using contactless service, such as robots making and bringing coffee to your table in a café, unmanned shops, and future interactions with public officials planned to take place in the metaverse. This would supposedly minimise infections, but at what cost to the socially meaningful relationships in communities? We risk averting a viral epidemic for a psychic epidemic.

Sometimes a job is just a job, and not a means to self-individuate. If your work is meaningful to you, then all the better. But jobs do provide dignity and a sense of self. When the ability of many people to earn a living was taken away, it could have contributed to a feeling of meaninglessness.

Jung proposed that religion can immunise people against a psychic epidemic through moral values and leadership, but it is not a substitute for a transpersonal relationship with the divine – an “inner, transcendent experience which alone can protect him from the otherwise inevitable submersion in the mass”. Faith alone can provide meaning which arms us against mass hysteria. Religion can be counter-productive when it is too close to the state:

“The disadvantage of a creed as a public institution is that it serves two masters: on the one hand, it derives its existence from the relationship of man to God, and on the other hand, it owes a duty to the State.”

Religion did not save us. Churches closed their doors at Easter, when Jesus Christ’s resurrection is remembered. Some of the faithful died without last rites. Religious leaders of all persuasions set aside the issue of foetal cell research and associated individual conscience in deference to the greater good. Going further, the Archbishop of Canterbury told Christians it was immoral not to be vaccinated.

“Vaccine Saves” was emblazoned on Christ the Redeemer in Rio de Janeiro. People sat spaced 2 metres apart in cathedrals awaiting vaccination, both medical miracle and ritual act of biomedical transubstantiation. Masks were more than totems in the latest culture war, they became the vestiture of the faithful, signalling belief and obedience. They emblemised a moral code based upon extending life, not securing your place in the afterlife. As sure as churches smell of incense, the nascent religion smells of hand sanitiser.

This essay has been quite preoccupied with Christianity, although I am not really a Christian. But Christianity, or at least faith, was central to Jung’s theories of self-individuation. It has also undergirded our society and everyday existence for many hundreds of years. We are bereft of great myths and arguably living in a post-religious vacuum – did this shape our response to Covid? If not Christianity, our interpretation of it has become antiquated in the present world. Given the response of the Church during Covid, people might perceive their spiritual leaders as empty vessels. With churches and other places of worship closed for so long and during important celebrations, congregants may wonder why they even need to return.

The question of human relationships and the cohesion of society is an urgent one. Not everyone will agree we have experienced mass hysteria on an almost global scale, but most will accept we are acutely divided on political and social fault lines. Human isolation renders us vulnerable to mass hysteria but also to the mass State which feeds upon atomised social units. To counter the danger we need to give thought to the human relationship from a psychological perspective. Not the cold, calculated view of the behavioural psychologist that predicts, anticipates and shapes behaviour, but the bonds of affection and genuine meaning that arise in a free society. Where love stops, power, violence and terror begin.

Democracy might be in retreat. New gods are raising their heads. We are changing gears from one aeon to the next, a new technological era. During one lifetime we have gone from a single bakelite telephone in the hallway on a curly cord, to encrypted messaging on smart phones and wifi. Within two generations we have moved from crystal radio to neuralinks. What will be next? How will our nature be suited and harmed by unprecedented technological advances in communication and lifestyle?

A novel virus disrupted our assumptions over our control over nature. We were not humble in the face of nature. We decided there was a potential existential crisis out of of our own human self-interest, but if the virus had wiped us out the sun would still rise tomorrow. The cruelties and folly of the pandemic response triggered my own political and ideological midlife crisis. I want to emerge from this examination of human nature believing in the sunset. I want to believe love wins. The way through the division is to embrace empathy. As Hannah Arendt said, “Forgiveness is the only way to reverse the irreversible flow of history.”

Beyond empathy, to combat a psychic epidemic we need meaning in our lives. Not an ersatz top-down solidarity, dreamt up by technocratic communications experts, but genuine, socially meaningful relationships, purpose and values. Lockdowns and restrictions squashed exactly what we need to flourish as human beings in order to counteract a psychic epidemic. As that crisis recedes, other dangers endure. Bad actors and paternalistic libertarians alike lack humility when they brazenly exploit our nature. We are buffeted by nudge, propaganda, and our passions. For the good of the collective, we must recapture meaning and values as individuals.

“Resistance to the organised mass can be effected only by the man who is as well organised in his individuality as the mass itself.” ~ Carl Jung

Reposted from the author’s substack

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

For reprints, please set the canonical link back to the original Brownstone Institute Article and Author.